| Sarawakfrom the Wikipedia | Read original article |

| Sarawak | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| State | |||

| Bumi Kenyalang (Land of the Hornbills) | |||

|

|||

| Nickname(s): Land of the Hornbills | |||

| Motto: "Bersatu, Berusaha, Berbakti" "United, Striving, Serving" |

|||

| Anthem: Ibu Pertiwiku (My Motherland) | |||

|

|||

| Capital | Kuching | ||

| Divisions | |||

| Government | |||

| • Yang Di-Pertua Negeri | Tun Pehin Sri Abdul Taib Mahmud | ||

| • Chief Minister | Tan Sri Datuk Patinggi Adenan Satem (BN) | ||

| Area[1] | |||

| • Total | 124,450 km2 (48,050 sq mi) | ||

| Population (2010)[2] | |||

| • Total | 2,420,009 | ||

| • Density | 19/km2 (50/sq mi) | ||

| Demonym | Sarawakian | ||

| Human Development Index | |||

| • HDI (2010) | 0.692 (high) (11th) | ||

| Time zone | MST (UTC+8) | ||

| Postal code | 93xxx to 98xxx | ||

| Calling code | 082 (Kuching), (Samarahan) 083 (Sri Aman), (Betong) 084 (Sibu), (Kapit), (Sarikei), (Mukah) 085 (Miri), (Limbang), (Marudi), (Lawas) 086 (Bintulu), (Belaga) |

||

| Vehicle registration | QA & QK (Kuching) QB (Sri Aman) QC (Kota Samarahan) QL (Limbang) QM (Miri) QP (Kapit) QR (Sarikei) QS (Sibu) QT (Bintulu) QSG (Sarawak State Government) |

||

| Brunei Sultanate | 15th century–1841[3] | ||

| Brooke dynasty | 1841–1946 | ||

| Japanese occupation | 1941–1945 | ||

| British Crown Colony | 1946–1963 | ||

| Independence | 22 July 1963[4] | ||

| Malaysia Agreement[5] | 16 September 1963a[6] | ||

| Website | www.sarawak.gov.my | ||

| a Despite the fact the foundation of the Federation of Malaysia is completed only on 16 September 1963, 31 August is celebrated as the Independence day of Malaysia. A similar observance can be found on many unified countries, including Tanzania, where the independence day was celebrated on 9 December (following the Independence of Tanganyika in 1961), even though Tanzania only came into existence in 26 April 1964 by joining Tanganyika and Zanzibar (known as Union Day in Tanzania), despite the fact that Zanzibar had already earlier gained its independence from the British on 10 December 1963.[7][8] While in Yemen, where the independence day is still celebrated on 30 November (based on the South Yemen independence from the United Kingdom on 1967). Even though the foundation of present-day Yemen was created by joining together Yemen Arab Republic (North Yemen) and People's Democratic Republic of Yemen (South Yemen) only on 22 May 1990 (celebrated as Unity Day In Yemen), in spite of North Yemen had earlier being granted its independence from the Ottoman Empire on 1 November 1918.[9][10][11] Equivalently in Malaysia, 16 September is recognised as Malaysia Day, a patriotic national-level public holiday to commemorate the foundation of Federation of Malaysia that joints North Borneo, Malaya, Sarawak and (previously) Singapore.[12][13] | |||

Sarawak (Malay pronunciation: [saˈrawaʔ]) is one of the two Malaysian states on the island of Borneo. It is also one of the founding members of the Malaysian federation alongside Crown Colony of North Borneo (Sabah), Singapore (expelled in 1965) and the Federation of Malaya (Peninsula Malaysia or West Malaysia). Like Sabah, this territory has an autonomous law especially in immigration, which differentiate it from the rest of the Malaysian Peninsula states. Today, the state is known as Bumi Kenyalang ("Land of the Hornbills").

Sarawak is situated on the northwest of Borneo, bordering the state of Sabah to the northeast, Indonesia to the south, and surrounding the independent state of Brunei. The administrative capital is Kuching, which has a population of 700,000.[14] Major cities and towns include Miri (pop. 350,000), Sibu (pop. 257,000) and Bintulu (pop. 200,000). As of the last census (2010), the state population was 2,420,009.[2]

Contents

History[edit]

Bruneian Empire[edit]

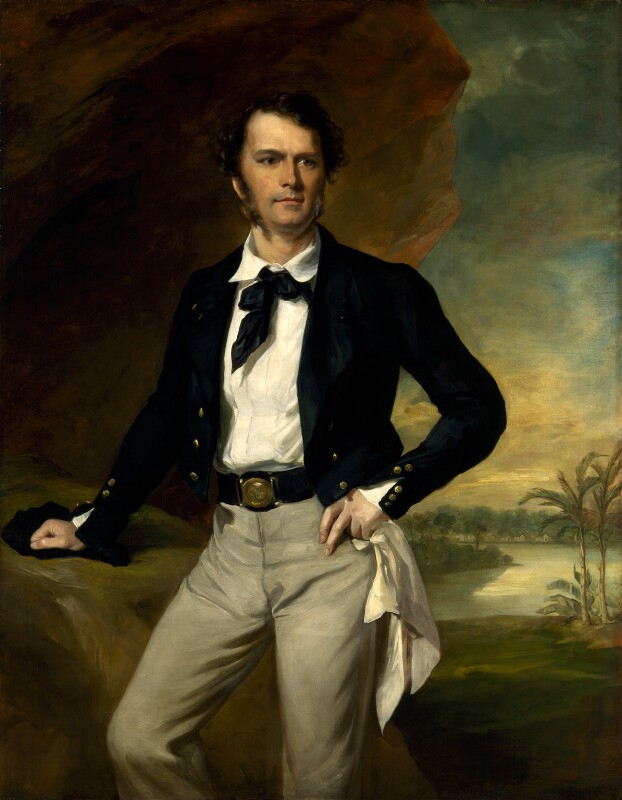

During the 15th century, the area was under the influence of the Bruneian Empire and was self-governed under Sultan Tengah.[3] The eastern seaboard of Borneo was charted, though not settled, by the Portuguese in the early 16th century.[4] The area of Sarawak was known to Portuguese cartographers as Cerava.[4] By the early 19th century, Sarawak had become a loosely governed territory under the control of the Brunei Sultanate.[4] During the reign of Pangeran Indera Mahkota in the 19th century, Sarawak was facing chaos.[4] Sultan Omar Ali Saifuddin II (1827–1852), the Sultan of Brunei, ordered Pangeran Muda Hashim in 1839 to restore order and it was during this time that James Brooke arrived in Sarawak.[4] Pangeran Muda Hashim initially requested assistance in the matter, but Brooke refused.[4] In 1841, Brooke paid another visit to Sarawak and this time he agreed to provide assistance. Pangeran Muda Hashim signed a treaty in 1841 surrendering Sarawak and Sinian to Brooke. On 24 September 1841, Pangeran Muda Hashim bestowed the title Governor on James Brooke. Then in 1846, he effectively became the Rajah of Sarawak and founded the White Rajah Dynasty of Sarawak after the death of Pengeran Muda Hashim.[15][16]

Brooke Dynasty[edit]

James Brooke was appointed Rajah by the Sultan of Brunei (by force of the British Government) on August 1846. Brooke ruled the territory, later expanded, across the western regions of Sarawak around Kuching until his death in 1868. His nephew Charles Anthoni Johnson Brooke became Rajah after his death; he was succeeded on his death in 1917 by his son, Charles Vyner Brooke, with the condition that Charles should rule in consultation with his brother Bertram Brooke.[17] The Sarawak territories were greatly enlarged under the Brooke dynasty, mostly at the expense of areas nominally under the control of Brunei. In practice Brunei had only controlled strategic river and coastal forts in much of the lost territory, so most of the gain was at the expense of Muslim warlords and of the de facto independence of local tribes.

The Brooke dynasty ruled Sarawak for a hundred years and became famous as the "White Rajahs", accorded a status within the British Empire similar to that of the rulers of Indian princely states. In contrast to many other areas of the empire, however, the Brooke dynasty was intent on a policy of paternalism to protect the indigenous population against exploitation. They governed with the aid of the Muslim Malay and enlisted the Ibans and other "Dayak" as a contingent militia. The Brooke dynasty also encouraged the immigration of Chinese merchants but forbade the Chinese to settle outside of towns to minimise the impact on the Dayak way of life. Charles Brooke, the second White Rajah of Sarawak, established the Sarawak Museum, the oldest museum in Borneo.

In the early part of 1941, preparations were afoot to introduce a new constitution, designed to limit the power of the Rajah and give the people of Sarawak a greater say in government. Despite this democratic intention, the draft constitution contained irregularities, including a secret agreement drawn up between Charles Vyner Brooke and his top government officials, financially compensating him via treasury funds.[4]

Second World War and occupation[edit]

Japan invaded Sarawak and occupied the island of Borneo in 1941, occupying Miri on 16 December and Kuching on 24 December, holding both territories for the duration of World War II until the area was secured by Australian forces in 1945 and managed under the British Military Administration. Charles Vyner Brooke formally ceded sovereignty to the British Crown on 1 July 1946, under pressure from his wife among others. In addition, the British Government offered a healthy pension to Brooke. Anthony Brooke, the designated heir, opposed the cession of the Rajah's territory to the British Crown, and was associated with anti-cessionist groups in Sarawak, consisting of a majority of the native members of the Council Negri (Parliament).

Post-Japanese Occupation[edit]

Anthony Brooke continued to claim sovereignty as Rajah of Sarawak. For this he was banished from Sarawak and he was allowed to return only seventeen years later, when Sarawak became part of Malaysia. Sarawak became a British Crown colony in July 1946, but Anthony's campaign continued. The Malays in particular resisted the cession to Britain, dramatically assassinating the second British governor, Sir Duncan George Stewart.

Independence and the Federation of Malaysia[edit]

Sarawak was officially granted independence on 22 July 1963, and later formed the federation of Malaysia with Malaya, North Borneo, and Singapore on 16 September 1963,[18][19] despite the initial opposition from parts of the population.[20][21] Sarawak was also a flashpoint during the Indonesia–Malaysia confrontation between 1962 and 1966.[22][23] Between 1962 and 1990, there was also a Communist insurgency in Sarawak.[24]

Geography[edit]

Having land area of 124,450 square kilometres (48,050 sq mi) spreading between latitude 0° 50′ and 5°N and longitude 109° 36′ and 115° 40′ E, it makes up 37.5% of the land of Malaysia. Sarawak also contains large tracts of tropical rainforest home to an abundance of plant and animal species but has been severely logged since the 1950s.

The state of Sarawak stretches for over 750 kilometres (470 mi) along the northeast coastline of Borneo, interrupted in the north by about 150 kilometres (93 mi) of Bruneian coast. Sarawak is separated from the Indonesian part of Borneo (Kalimantan) by ranges of high hills and mountains that are part of the central mountain range of Borneo. These get higher to the north and culminate near the source of the Baram River with the steep Mount Selidang (4504 ft) at central plateau of Usun Apau, Mount Batu Lawi, Mount Mulu in the park of the same name and Mount Murud with the highest peak in Sarawak.

The major rivers from the south to the north include the Sarawak River, Lupar River, Saribas River, and Rajang River, which is the longest river in Malaysia at 563 kilometres (350 mi). The Baleh River branch, the Baram River, and the Limbang River drains into the Brunei Bay as it divides the two parts of Brunei and the Trusan River. The Sarawak river is 2,459 square kilometres (949 sq mi) in area and is the main river flowing through the capital of Kuching.

Sarawak can be divided into three natural regions. The coastal region is rather low lying flat country with large extents of swamps and other wet environments. The hill region provides most of the easily inhabited land and most of the larger cities and towns have been built in this region. The ports of Kuching and Sibu have been built some distance from the coast on rivers. Bintulu and Miri are close to the coastline where the hills stretch right to the South China Sea. The third region is the mountain region along the border and with the Kelabit (Bario), Murut (Ba Kelalan) and Kenyah (Usun Apau) highlands in the north.

Demographics[edit]

Population[edit]

As of the 2010 census, the population of Sarawak was 2,399,839, making it the 4th most populous state in Malaysia.[25] Due to the large area of Sarawak, it has the lowest population density in Malaysia, which stands at 22 people per km2. Sarawak also has some of the lowest population growth in Malaysia.

Ethnic groups[edit]

Sarawak has more than 40 sub-ethnic groups, each with its own distinct language, culture and lifestyle. Cities and larger towns are populated predominantly by Malays, Melanaus, Chinese, Indians, and a smaller percentage of Ibans and Bidayuhs who have migrated from their home villages to look for employment.

Generally, Sarawak has six major ethnic groups namely Iban, Chinese, Malay, Bidayuh, Melanau, and Orang Ulu.[26] Several minor ethnic groups include Kedayan, Javanese, Bugis, Murut, and Indian. Unlike Indonesia, the term Dayak is not officially used to address Sarawakian's native ethnicity.

Iban[edit]

The Ibans comprise the largest percentage (almost 30%) of Sarawak's population.[25] Iban is native to Sarawak and Sarawak has the highest number of Ibans in Borneo.

The large majority of Ibans practise Christianity. However, like most other ethnic groups in Sarawak, they still observe many of their traditional rituals and beliefs. Sarawak celebrates colourful festivals such as the generic Gawai Dayak (Harvest Festival), Gawai Kenyalang (Hornbill Festival), Gawai Burong (Bird Festival), Gawai Tuah (Luck Festival), Gawai Pangkong Tiang (House Post Banging Festival), Gawai Tajau (Jar Festival), Gawai Sakit (Healing Festival) and Gawai Antu (festival of the dead).

Chinese[edit]

Sarawakian Chinese are mostly made up of Han Chinese being 99.99% classified as ethnic Han as Chinese is a loose term which inclusive of all the 55 ethnic group of People's Republic of China. Chinese pioneers first came to Sarawak as traders and explorers in the 6th century. Today, they make up 24% of the population of Sarawak[25][26] and consist of communities built from the economic migrants of the 19th and early 20th centuries. They are classified as a non-Bumiputera ethnic group.

The Sarawak Chinese belong to a wide range of dialect groups, the most significant being Cantonese, Foochow, Hakka, Hokkien, Teochew, Hainanese, and Puxian Min. The Chinese maintain their ethnic heritage and culture and celebrate all the major cultural festivals, most notably the Chinese New Year and the Hungry Ghost Festival. The Sarawak Chinese are predominantly Buddhists.

Ethnic Chinese were encouraged to settle in Sarawak because of their commercial and business acumen. The biggest dialect group is the Hokkien people; many originated from Choanchew, Chiangchew, Longhai, Kinmen, Amoy and Taiwan.

The Hakka people, Teochew people, Henghua people, Hainan people, Shanghainese people and Cantonese people represent a minority of the Chinese population. Despite their small numbers, the Hokkien have a considerable presence in Sarawak's private and business sector, providing commercial and entrepreneurial expertise and often operating joint business ventures with Malaysian Chinese entreprises.[27] A notable person namely Ong Tiang Swee safeguard the interest and welfare of the Chinese communities in Sarawak back in the old days, he was considered as Kapitan China.

Some Chinese settled in Sarawak after the Sun Yat Sen led Kuomintang lost the civil war in 1949 against the Communist Party of China namely Longhai Campaign.[28][29]

In 1963, when Sarawak helped Malaya to form Malaysia, most of the Chinese which hails from Coastal cities from Xiamen, Guangzhou, Quanzhou automatically gained Malaysian citizenship despite having the Republic of China citizenship under Kuomintang (not to be confused with Communist Party of China).[30]

Fuzhou people came in Sarawak in 1901 from Fuzhou, Fujian due to numerous violent incident such as the infamous Boxer Rebellion that occur in the Qing Dynasty in 1899.[31] During the boxer rebellion many Chinese Christian are murdered in brutality and as well as women and children are being punished for their faith, as of this action the Qing Dynasty supported the causes, Wong Nai Siong a Christian leader, led them to a safer place to live and to create a community by agreeing with terms and contract with late Charles Brooke, Rajah of Sarawak and later allocated them to a nearby town called Sibu and decided to name it the New Foochow Settlement. However, due to the sizeable presence of other Chinese sub-ethnic groups such as the Hokkiens, Hakka, and the Cantonese they ultimately retained the original name of the area.[32]

Sarawak Hakka were particularly from Jiexi County, Guangdong. As most of these Hakka spoke Hopo Hakka which differs from the other Hakka.

Malay[edit]

The Malays make up 23% of the population in Sarawak.[25] They mostly populate the southern region and urban areas of Sarawak. Despite being Malays, Sarawak Malay has a distinct culture and language to that of other Malays in Peninsular Malaysia. They speak local variant of Bahasa Melayu Sarawak (or Sarawak Malay), and been classified as Bumiputera Sarawak in Sarawak Gazette.[33]

Melanau[edit]

The Melanaus have been thought to be amongst the original settlers of Sarawak.[34] They make up 6% of the population in Sarawak.[25]

Today most of the Melanaus community profess Islam and Christianity, though they still celebrate traditional animist festivals such as the annual Kaul festival.

Bidayuh[edit]

Concentrated mainly on the West end of Borneo, the Bidayuhs make up 8% of the population in Sarawak.[25]

The Bidayuhs speak a number of different but related dialects. Some Bidayuhs speak either English or Sarawak Malay as their main language. While some of them still practise traditional religions, the majority of modern-day Bidayuhs have adopted the Christian faith. Another ethnic associated to Bidayuh is Salako, classified as Bidayuh by the Malaysian government for political convenience.

Orang Ulu[edit]

Orang Ulu is an ethnic group in Sarawak. The various Orang Ulu ethnics together make up roughly 6% of Sarawak's population. The phrase Orang Ulu means upriver people and is a term used to collectively describe the numerous tribes that live upriver in Sarawak's vast interior. Such groups include the major Kenyah and Kayan people, and the smaller neighbouring groups of the Kajang, Kejaman, Punan, Ukit, and Penan. Nowadays, the definition also includes the down-river tribes of the Lun Bawang, Lun Dayeh, "mean upriver" or "far upstream", Berawan, Saban as well as the plateau-dwelling Kelabits. Orang Ulu is a term coined officially by the government to identify several ethnics and sub-ethnics who live mostly at the upriver and uphill areas of Sarawak. Most of them live in the district of Baram, Miri, Belaga, Limbang, and Lawas.

A vast majority of the Orang Ulu tribe are Christians but traditional religions are still practised in some areas.

Some of the major tribes making up the Orang Ulu group include:

Others[edit]

Other minority ethnic groups residing in Sarawak are the Kedayan ethnic groups and also the Punan Bah people (in fact is a collective of obscure and unaccounted ethnic communities grouped together as a single ethnic entity), and also non-Bumiputera ethnic groups, which are the Indian and Eurasian.

The Kedayan are an ethnic group residing in parts of Sarawak. The Kedayan language is spoken by more than 37,000 people in Sarawak, with most of the members of the Kedayan community residing in Lawas, Limbang, Miri, and Sibuti areas. Unlike its Peninsular counterpart, Sarawakians of Indian descent are small in number and have assimilated very well to the other communities. Eurasians continues to be the smallest among the minority ethnic groups in Sarawak, mostly due to assimilation and interracial marriages. The Punan Bah communities are usually located in areas that encompass the borders of Sarawak, Sabah, Brunei, and Indonesia. More studies need to be carried out about them, as they are one of the lesser known group in the state.

Religion[edit]

As of 2010 the population of Sarawak disregarding foreign immigrants is 44.0% Christian, 30.0% Muslim, 13.5% Buddhist, 6.0% Taoist or Chinese religion follower, 3.1% follower of other religions, and 2.6% non-religious.

Sarawak is the only state in Malaysia where Christians outnumber Muslims. Major Christian denominations in Sarawak are the Roman Catholics, Anglicans, Methodists, Borneo Evangelical Mission (BEM or Sidang Injil Borneo, S.I.B.), and Baptists. Many Sarawakian Christians are non-Malay Bumiputera, ranging from Iban, Bidayuh, Orang Ulu and Melanau. Islam is the second largest religion in Sarawak. Many Muslims are from Malay, Melanau, and Kedayan ethnic groups. Buddhism is the third largest, predominantly practised by Chinese Malaysians. Taoism and Chinese Folk Religion are together the fourth largest religious group, also represented by ethnic Chinese. Other minor religions in Sarawak are Baha'i, Hinduism, Sikhism, and animism. Many Dayaks especially the Ibans, continue to practice their ethnic religion, particularly with dual marriage rites and during the important harvest and ancestral festivals such as Gawai Dayak, Gawai Kenyalang and Gawai Antu. Other ethnics who have trace number of animism followers are Melanau and Bidayuh.

Government[edit]

The parliament of Sarawak is the Sarawak State Legislative Assembly.

Politics of Sarawak[edit]

The first political party, Sarawak United Peoples' Party (SUPP) was established in 1959 followed by Parti Negara Sarawak (PANAS) in 1960, and Sarawak National Party (SNAP) in 1961. Other parties such as Barisan Ra'ayat Jati Sarawak (BARJASA), Sarawak Chinese Association (SCA), and Parti Pesaka Sarawak (PESAKA) later appeared by 1962.

Sarawak has been a political stronghold of ruling Alliance Party and later Barisan Nasional (BN) coalition since its independence in 1963. Stephen Kalong Ningkan (SNAP) was the first Chief Minister of Sarawak from 1963 to 1966 following his landslide winnings of three tier system of local authority elections. He was later ousted in 1966 by Tawi Sli (PESAKA) with the help of Malaysian federal government, causing 1966 Sarawak constitutional crisis.[36]

Sarawak political climate was stable since then until the Ming Court Affair which lasted from 1987 to 1991. Ming Court Affair was a political coup initiated by Abdul Taib Mahmud's uncle in order to topple the Taib led Sarawak BN coalition. However, the coup was unsuccessful and Taib was able to retain his chief minister post.[37] The issue of human rights of Penan and deforestation in Sarawak became an international environmental issue when Swiss activist Bruno Manser entered Sarawak from 1984 until 2000 where he brought himself into direct conflict with the Sarawak state government.[38]

The year 1970 saw the completion the first Sarawak state election where members of Council Negri (now Sarawak State Legislative Assembly) was directly elected by the voters. This election also marks the beginning of ethnic Melanau domination in Sarawak politics at first by Abdul Rahman Ya'kub and followed by his nephew Abdul Taib Mahmud. In the same year, North Kalimantan Communist Party (NKCP) was formed which mounted guerilla warfare against the newly elected Sarawak state government. The party was dissolved after the signing of peace agreement in 1990.[24] The year 1973 saw the demise of SCA after it was booted out by the government coalition and the birth of Parti Pesaka Bumiputera Bersatu (PBB).[39] PBB was formed by the merger of three parties namely PANAS, BARJASA, and PESAKA. This party would later become the backbone of Sarawak BN coalition, currently holding 35 out of 71 state assembly seats after 2011 Sarawak state election.

A splinter party named Parti Bansa Dayak Sarawak (PBDS) broke off from SNAP in 1983 due to leadership tussle. PBDS would later dissolved in 2004 also due to another leadership crisis. Parti Rakyat Sarawak (PRS), a splinter party from PBDS, was formed after that in 2004. PRS is currently a component party in Barisan Nasional (BN). SNAP was deregistered in 2002. Sarawak Progressive Democratic Party (SPDP), another splinter party from SNAP, was formed after that in 2002 which would later become a component party of BN. The SNAP deregistration would later be reversed by Court of Appeal in June 2010. However, the revival was short-lived. SNAP was deregistered again in January 2013 by the verdict of Federal Court of Malaysia.[40] In 2010, another splinter party named Sarawak Workers Party (SWP) emerged to absorb dissidents from PRS. In 2014, Parti Tenaga Rakyat Sarawak (Teras) was formed following a split in SUPP, a component party in BN coalition.[41]

In 1978, Democratic Action Party (DAP) was the first Peninsular-based party to open its branches in Sarawak.[39] This party derived majority of its support from urban centres such as Miri, Bintulu, Sibu, and Kuching since 2006 state election and become the largest opposition party in Sarawak, currently holding 12 out of 71 state assembly seats.[42] In 2010, it forms Pakatan Rakyat coalition with Parti Keadilan Rakyat (PKR) and Parti Islam Se-Malaysia (PAS) where the latter 2 parties entered Sarawak only between 1996 and 2001.[43] Sarawak is the only state in Malaysia where Peninsular-based component parties in BN coalition especially UMNO has not entered Sarawak.[44]

Administrative divisions[edit]

Unlike other states in Malaysia, Sarawak is divided into divisions rather than districts. Each division is headed by one resident. Currently, the state been divided into 11 divisions:

Administrative districts[edit]

The divisions are further divided into districts, each of which is headed by a district officer; and each district is divided into sub-districts, which every sub-districts headed by an administrative officer. Currently, there are around 31 districts in the state.

| Division | District | Subdistrict |

|---|---|---|

| Kuching | Kuching | Siburan, Padawan |

| Bau | ||

| Lundu | Sematan | |

| Samarahan | Samarahan | |

| Asajaya | ||

| Simunjan | Sebuyau | |

| Serian | Tebedu | |

| Sri Aman | Sri Aman | Lingga, Pantu |

| Lubok Antu | Engkilili | |

| Betong | Betong | Pusa, Spaoh, Debak, Maludam |

| Saratok | Roban, Kabong, Budu | |

| Sibu | Sibu | |

| Kanowit | ||

| Selangau | ||

| Mukah | Mukah | Balingian |

| Dalat | Oya | |

| Daro | Belawai | |

| Matu | Igan | |

| Miri | Miri | Subis, Niah-Suai |

| Marudi | Beluru, Long Lama | |

| Bintulu | Bintulu | Sebauh |

| Tatau | ||

| Limbang | Limbang | Ng. Medamit |

| Lawas | Sundar, Trusan | |

| Sarikei | Sarikei | |

| Meradong | ||

| Julau | ||

| Pakan | ||

| Kapit | Kapit | Nanga Merit |

| Song | ||

| Belaga | Sungai Asap | |

Energy[edit]

The state of Sarawak has introduced the Sarawak Corridor of Renewable Energy (SCORE), a new development corridor launched on 11 February 2008. It is one of the five regional development corridors throughout Malaysia that aims to transform Sarawak into a developed state by 2020 by accelerating the state's economic growth, as well as improving the quality of life for the people of Sarawak.[45][46]

Overseas interest is key to the development of SCORE with investment in the aluminium, the polysilicon, and minerals-based industries as well as agriculture including aquaculture and halal.[clarification needed]

Focusing on five major growth nodes, Tanjung Manis, Samalaju, Mukah, Baram, and Tunoh, SCORE singles out 10 key industries for development.[47] These include tourism, oil, aluminium, metals, glass, fishing, aquaculture, livestock, forestry, ship building and palm oil.[48] Investors are being drawn to the region because it is rich in energy resources, with an energy potential of 28,000 MW, of which 20,000 MW are in hydropower, 5,000 MW in coal-fired plants, and the remaining 3,000 MW in other energy sources including biofuel. This allows Sarawak to price its energy competitively and encourage investments in power generation and energy-intensive industries that will stimulate strong industrial development in the corridor.[49]

SCORE is developing a vast area that stretches 320 kilometres along Sarawak’s coast from Tanjung Manis to Samalaju and extends all the way into the extensive and remote hinterlands where two rural growth nodes, Baram and Tunoh, will also be developed.[50] To connect urban centres across the central region with the rest of Sarawak, new roads will be created to provide more efficient transport of goods, access to resources and human capital.[51]

According to environmental initiatives like Save Sarawak Rivers, the targeted construction of 50 hydroelectric dams will seriously effect Sarawak's natural environment and wildlife: the Baram dam alone would flood 400 square kilometres of forest and farmland and 20,000 native people would have to be resettled.[52]

Economy[edit]

Sarawak has an abundance of natural resources. LNG and petroleum have provided the mainstay of the Malaysia federal government's economy for decades while the State of Sarawak only gets a 5% royalty share from it. Sarawak is also one of the world's largest exporters of tropical hardwood timber and is the major contributor to Malaysian exports. The last UN statistics estimated Sarawak's sawlog exports at an average of 14,109,000 m³ between 1996 and 2000.[53] In 2010, Sarawak had the 3 third largest state economy in Malaysia after Selangor and Johor with a total nominal GDP of RM 50,804M (USD$16,542M).[54] Sarawak is also the 2nd largest state in terms of GDP per capita after Penang with RM 33,307.00 (USD$10,845.00) in 2010.[55]

Tourism[edit]

Tourism plays a major role in the state's economy. In 2012, Sarawak was visited by 4 million tourists, both international and domestic.[56] As for 2013, the state is targeting 6 million visitors. This is in line with more direct flights from countries such as Japan and South Korea. The Sarawak Hornbill Tourism Award is held each year to appreciate the best in the tourism sector of the state. Some of the most popular tourist attractions are Kuching city, Gunung Mulu National Park, the Rainforest World Music Festival (RWMF) and many more. The RWMF is the region's premier "world music" event, attracting more than 20,000 music fans.[57] Malaysia will showcase the Sarawak tourism industry in 2014 when it hosts the ASEAN Tourism Forum in Kuching, the Sarawak state capital. It will be the first international tourism event in Malaysia for 2014 and will bring together tourism ministers and heads of national tourism organisations from ASEAN and the region.[58]

Environment[edit]

Agriculture, logging, and land usage[edit]

Sarawak's rainforests have been gradually depleted by the demand driven by the logging industry and the following introduction of palm oil plantations. They possibly are going to be destroyed by 2020.[59] Many of Sarawak's rural communities have felt changes affected by the economic activity of these industries. Peaceful protests and timber blockades between native communities and logging companies are common, often resulting in preventive police action. The Penan, Borneo's nomadic hunter-gatherers have been most affected by these changes, complaining of illness through polluted rivers, game depletion resulting in widespread hunger and loss of traditional medicines and forest products. Their resistance to logging companies culminated in a series of protests and timber blockades in the 1990s, of which many were dismantled by the Police, within the remit of the law. The Penan claim that their rights are not respected by the State nor by logging companies.[60] Another example, the native customary rights court case of Rumah Nor in the Kemena Basin gave rural communities engaged in subsistence farming hope for continued communal use of land reserves. Although the Court of Appeal ruled against Rumah Nor on the grounds that they had not produced sufficient evidence for their claim, it nevertheless upheld the principles stated by the lower court. These principles are the basis of not only Rumah Nor's claim, but of the claims of all Sarawak's native communities as that native customary rights are not created by legislation, although they can be extinguished by legislation, on condition of adequate compensation, and these communities have a territory including forest reserves and rivers, and farmland, including land under fallow. Thus although the Court of Appeal ruled against Rumah Nor's specific claims, it upheld the lower court's ruling in favour of Rumah Nor with regard to the general principles.

Malaysia's deforestation rate is increasing faster than anywhere else in the world. Statistics estimate Sarawak's forests have been depleted but there is no definitive study to know how much. Malaysia's deforestation rates overall are among the highest in Asia, jumping almost 86 percent between the 1990–2000 period and 2000–2005. In total, Malaysia lost an average of 1,402 km2 —0.65 percent of its forest area—per year since 2000.[61] The rainforest is the habitat of endangered animals, including borneo pygmy elephant, proboscis monkey, orangutans and rhinoceroses.[62][63][64][65][66]

Conservation[edit]

The Sarawak government announced that they are stepping up their effort for wildlife conservation and protection. A programme has been put in place by Sarawak government to save the flora and fauna affected by the construction of the Bakun Dam.[67] Other programmes include the Heart 2 Heart orangutan campaign which invites the public to get involved with orangutan conservation; orang-utan and turtle adoption; protection of the dugong and the Irrawaddy dolphin, which are both endangered species; and the Reef Ball project that will rehabilitate Sarawak's ocean ecosystem by placing artificial reef modules in the sea to form new habitats.[67]

In 1992, International Tropical Timber Organization (ITTO) also financed the establishment of Lanjak Entimau Wildlife Sanctuary which now houses about 4000 orangutans. This wildlife sanctuary also aimed to improve the livelihood of the rural population and to reduce their dependence on forests.[68]

Places of interest[edit]

The Gunung Mulu National Park is home to one of the longest networks of caves in the world and the world's largest underground chamber, the Sarawak Chamber. Key attractions include Deer Cave and Clear Water Cave. The massive caves here are home to millions of bats and cave swiftlets.[69]

Known as the 'Living Museum', the Sarawak Cultural Village was set up to preserve and showcase Sarawak's cultural heritage. Get introduced to local culture and lifestyle by the approximately 150 people living in the village through the demonstration of daily living. The village also has a theatre, where you can enjoy multicultural dance performances.[70]

Bako National Park is Sarawak's oldest park, established in 1957 and covers and area of 27 km2. Known for its extraordinary natural scenery, habitats, plants and wild life, it is also the home to approximately 275 rare proboscis monkeys, found only in Borneo.[71]

The Gunung Gading National Park is the home to the spectacular Rafflesia, the largest flower in the world that can grow up to one metre in diameter. Originally a closed conservation zone, the park opened to the public in 1994 while being closely watched by the National Parks Department.[72]

The Matang Wildlife Centre is a large enclosed area of rainforest and home to endangered wildlife with a training programme to teach Orang Utans, who have been orphaned or rescued from captivity, how to survive in the wild. There are also Sun Bears, Sambar Deer, Civet cats as well as three large aviaries that house Sea Eagles, Hornbills and other birds.[73]

The Niah National Park covers a vast swathe of 3,140 hectares of peat swamp, dipterocarp forests, as well as the massive limestone outcroppings within which the giant Niah caves are concealed. In 1958, archaeologists discovered evidence of human occupation of the caves dating back some 40,000 years.[74]

Similajau National Park was gazetted in 1978, and covers 7,064 hectares of virgin coastal forest, starting from Sungai Likau in the south to Similajau River in the north. It is abundant in flora and fauna with 24 recorded species of mammals, such as gibbons, banded langurs and long-tailed macaques, and 230 species of birds, which include hornbills and migratory water birds like Storms Stork.[75]

The main attraction of the Lambir Hills National Park is its beautiful waterfalls, which are the Latak Waterfall, Pantu Waterfall, Nibong Waterfall, Pancur Waterfall, Tengkorong Waterfall and Dinding Waterfall. There are around 1,173 tree species in the park alone, with 286 genera and 81 tree families. Wild animals can also be found in the deeper parts of the park, especially monkeys, sun bear, pangolin and bats.[76]

The Kuching Cat Museum hosts 2000 exhibits, artefacts, statues about cats from all over the world. It is owned by the Kuching North City Hall (DBKU).[77]

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ "Laporan Kiraan Permulaan 2010". Jabatan Perangkaan Malaysia. p. 27. Archived from the original on 27 December 2010. Retrieved 24 January 2011.

- ^ a b "Laporan Kiraan Permulaan 2010". Jabatan Perangkaan Malaysia. p. iv. Archived from the original on 27 December 2010. Retrieved 24 January 2011.

- ^ a b Rozan Yunos (28 December 2008). "Sultan Tengah — Sarawak's first Sultan". The Brunei Times. Archived from the original on 3 April 2014. Retrieved 3 April 2014.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Frans Welman. Borneo Trilogy Sarawak: Volume 2. Booksmango. pp. 132–134–177. ISBN 978-616-245-089-1. Retrieved 28 August 2013.

- ^ Malaysia Act 1963. Retrieved on 12 August 2011.

- ^ Agreement relating to Malaysia between United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, Federation of Malaya, North Borneo, Sarawak and Singapore

- ^ Independence Day - Tanzania

- ^ Tanzania National Profile

- ^ AME.info.com Yemen Public Holidays

- ^ Worldstatemen.org Yemen

- ^ Independence Day - Yemen

- ^ The Star

- ^ Malaysian Public Holidays

- ^ (2006 census; Kuching City South – 143,500; Kuching City North – 133,600; Padawan- 3rd Mile/ 7th Mile/ 10th Mile – 302,800)

- ^ James Leasor (1 January 2001). Singapore: The Battle That Changed the World. House of Stratus. pp. 41–. ISBN 978-0-7551-0039-2.

- ^ Alex Middleton (June 2010). "Rajah Brooke and the Victorians". The Historical Journal 53 (2). pp. 381–400. doi:10.1017/S0018246X10000063. ISSN 1469-5103. Retrieved 24 December 2014.

- ^ [1][dead link]

- ^ United Nations list of Non-Self-Governing Territories, North Borneo and Sarawak. Un.org (14 December 1960). Retrieved on 12 August 2011.

- ^ United Nations Member States. Un.org. Retrieved on 12 August 2011.

- ^ UN General Assembly 15th Session – The Trusteeship System and Non-Self-Governing Territories (pages:509–510). Retrieved on 12 August 2011.

- ^ UN General Assembly 18th Session – the Question of Malaysia (pages:41–44). Retrieved on 12 August 2011.

- ^ United Nations Treaty Registered No. 8029, Manila Accord between Philippines, Federation of Malaya and Indonesia (31 July 1963). Retrieved on 12 August 2011.

- ^ United Nations Treaty Series No. 8809, Agreement relating to the implementation of the Manila Accord. Retrieved on 12 August 2011.

- ^ a b Chan, Francis; Wong, Phyllis (16 September 2011). "Saga of communist insurgency in Sarawak". The Borneo Post. Retrieved 10 January 2013.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Negeri: Sarawak: Total population by ethnic group, sub-district and state, Malaysia, 2010". Statistics.gov.my. Retrieved 14 November 2012.

- ^ a b "Christmas Book Festival to be held in East Malaysia". assistnews.net. Retrieved 1 December 2012.

- ^ Richter, Frank-Jürgen, ed. (1999). "Overseas Chinese and Overseas Indian Business Networks". Business Networks in Asia: Promises, Doubts, and Perspectives. Greenwood. ISBN 9781567203028. Retrieved 16 May 2012.

- ^ Pike, John. "Chinese Civil War". Global Security. Retrieved 14 November 2012.

- ^ "Chiang Kai Shiek". Sarawakiana. Retrieved 28 August 2012.

|first1=missing|last1=in Authors list (help)[unreliable source?] - ^ Jan Voon, Cham. "Kuomintang's influence on Sarawak Chinese". University of Malaysia Sarawak (UNIMAS). Retrieved 28 August 2012.

- ^ Taylor, Isaac. "Boxer Rebellion". The Burke Library Archives (Columbia University Libraries) Union Theological Seminary, New York. Retrieved 11 November 2013.

- ^ SuMin, Lim. "Pastor Wong Nai Siong". Retrieved 11 November 2013.[unreliable source?]

- ^ Faisal Syam Abdol Hazis, Mohd (2012). Domination and Contestation: Muslim Bumiputera Politics in Sarawak. ISBN 9789814311588.

- ^ Gomiri. Gomiri. Retrieved on 12 August 2011.

- ^ "2010 Population and Housing Census of Malaysia". Department of Statistics, Malaysia. Retrieved 17 June 2012. p. 13

- ^ Morrison, A (1993). In Fair Land Sarawak: Some Recollections of an Expatriate Official. SEAP Publications. p. 118-120. ISBN 0-87727-712-5. Google Book Search. Retrieved 19 June 2014.

- ^ "SPECIAL REPORT: The Ming Court Affair (subscription required)". Malaysiakini. 9 January 2013. Retrieved 23 June 2014.

- ^ Elegant, Simon (3 September 2001). "Without a Trace". Time magazine Asia. Retrieved 14 August 2014.

- ^ a b Chin, James (1996). "The Sarawak Chinese Voters and Their Support for the Democratic Action Party (DAP)". Southeast Asian Studies (Kyoto University Research Information Repository) 34 (2): 387–401. Retrieved 19 June 2014.

- ^ Tawie, Joseph (9 January 2013). "SNAP faces more resignations over BN move". Free Malaysia Today. Retrieved 19 June 2014.

- ^ Mering, Raynore (23 May 2014). "Analysis: Party loyalty counts for little in Sarawak". The Malay Mail. Retrieved 19 June 2014.

- ^ "BN retains Sarawak, Taib sworn in as CM". Free Malaysia Today. 16 April 2011. Retrieved 23 June 2014.

- ^ Chua, Andy (24 April 2010). "DAP: Sarawak Pakatan formed to promote two-party system". The Star (Malaysia) (Star Publications). Retrieved 23 June 2014.

- ^ Ling, Sharon (14 February 2014). "Muhyiddin: Umno need not be in Sarawak". The Star (Malaysia). Retrieved 23 June 2014.

- ^ Skor Career. Skor Career. Retrieved on 12 August 2011.

- ^ Sky Scraper City. Sky Scraper City. Retrieved on 12 August 2011.

- ^ Live Trading News. Live Trading News. Retrieved on 12 August 2011.

- ^ Scan News. Scanenews.blogspot.com (12 February 2010). Retrieved on 12 August 2011.[unreliable source?]

- ^ Recoda[dead link]

- ^ Mocs Sarawak. Mocsarawak.wordpress.com (29 September 2010). Retrieved on 12 August 2011.[unreliable source?]

- ^ Small Business report. Smallbusinesspost.wordpress.com (25 October 2009). Retrieved on 12 August 2011.[unreliable source?]

- ^ "Hydro Tasmania Out of Sarawak: Save Sarawak Rivers: About". Retrieved 5 December 2012.

- ^ An overview of forest products statistics in South and Southeast Asia. Fao.org. Retrieved on 12 August 2011.

- ^ "GDP by State and Kind of Economic Activity for the year 2010 at Constant Price 2000". Department of Statistics, Malaysia. Retrieved 15 January 2013.

- ^ "GDP Per Capita by State for the year 2008-2010 at Current Price". Department of Statistics, Malaysia. Retrieved 15 January 2013.

- ^ "Kuching to host Routes Asia 2014". Investvine.com. 5 April 2013. Retrieved 5 April 2013.

- ^ Sarawak fest certain to be a rare treat. Bangkok Post (22 February 2011). Retrieved on 12 August 2011.

- ^ "Sarawak to fly the ATF flag next year". TTGmice. Retrieved 23 January 2013.

- ^ http://www.theguardian.com/environment/2011/feb/02/malaysian-palm-oil-forests[not in citation given]

- ^ Bruno Manser Fonds. Bmf.ch. Retrieved on 12 August 2011.

- ^ Malaysia: Environmental Profile. Rainforests.mongabay.com. Retrieved on 12 August 2011.

- ^ "Rainforest is destroyed for palm oil plantations on Malaysia's island state of Sarawak (Image 1)". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 21 August 2014.

- ^ "Rainforest is destroyed for palm oil plantations on Malaysia's island state of Sarawak (Image 2)". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 21 August 2014.

- ^ "Rainforest is destroyed for palm oil plantations on Malaysia's island state of Sarawak (Image 3)". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 21 August 2014.

- ^ "Sumatran Orangutans’ rainforest home faces new threat". Agence France-Presse. The Borneo Post. 5 May 2013. Retrieved 21 August 2014.

- ^ Meijaard, E., Nijman, V. & Supriatna, J. (2008). Nasalis larvatus. In: IUCN 2008. IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Retrieved 4 January 2009.

- ^ a b Wildlife Conservation Top Priority for Sarawak Government

- ^ 25 success stories page 44-45 International Tropical Timber Organization

- ^ "Gunung Mulu National Park". Tourism Malaysia. Retrieved 23 May 2014.

- ^ "Sarawak Cultural Village". Tourism Malaysia. Retrieved 23 May 2014.

- ^ "Bako National Park". Tourism Malaysia. Retrieved 23 May 2014.

- ^ "Gunung Gading National Park". Tourism Malaysia. Retrieved 23 May 2014.

- ^ "Matang Wildlife Centre". Tourism Malaysia. Retrieved 23 May 2014.

- ^ "Niah National Park". Tourism Malaysia. Retrieved 23 May 2014.

- ^ "Similajau National Park". Tourism Malaysia. Retrieved 23 May 2014.

- ^ "Lambir Hills National Park". Tourism Malaysia.

There are around 1,173 tree species in the park alone, with 286 genera and 81 tree families making Lambir one of the more diversified forests in Malaysia. Wild animals can also be found in the deeper parts of the park, especially monkeys, sun bear, pangolin and bats.

- ^ "Cat Museum". Tourism Malaysia. Retrieved 23 May 2014.

Further reading[edit]

- James Chin, (2014) Federal-East Malaysia Relations: Primus-Inter-Pares?, in Andrew Harding and James Chin (2014) 50 Years of Malaysia: Federalism Revisited (Singapore: Marshall Cavendish) pp. 152–185

- James Chin, “Forced to the periphery: Recent Chinese politics in East Malaysia” in Leo Suryadinata & Lee Hock Guan (ed) Malaysian Chinese: Recent Developments and Prospects (Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asia Studies, 2012) pp. 109–124

- Gudgeon, L. W. W. (1913), British North Borneo. London, Adam and Charles Black.

- Runciman, Steven (1960). The White Rajahs: A History of Sarawak from 1841 to 1946, Cambridge University Press.

- Chin, Ung Ho (1997), Chinese Politics in Sarawak: A Study of the Sarawak United People's Party (SUPP), (Kuala Lumpur, New York: Oxford University Press, 1997) (ISBN 983-56-0039-2).

- Barley, Nigel (2002), White Rajah, London, Brown Little/Abacus.

- Cramb, R. A. (2007), Land and Longhouse: Agrarian Transformation in the Uplands of Sarawak, Hawaii University Press

- Julitta Lim Shau Hua: „Pussy's in the well“ : Japanese occupation of Sarawak, 1941–1945. Research and Resource Centre SUPP Headquarters, Kuching 2006, ISBN 983-41998-2-1

- Brooke, Sylvia (The last Ranee of Sarawak), (1970), Queen of the Headhunters. William Morrow Co.

- Palmer, Gladys, (1929) Relations & Complications. Being the Recollections of H.H. The Dayang Muda of Sarawak. Foreword by T.P. O'Connor. Ghost-written by Kay Boyle. London, John Lane Co.

- Urmenyhazi, Attila - DISCOVERING NORTH BORNEO a short travelogue on Sarawak & Sabah by the author (2007). National Library of Australia, Canberra, record ID: 4272798. Call Number: NLp 915 953 U77.

- James Chin. “The More Things Change, The More They Remain The Same”, in Chin Kin Wah & D. Singh (eds.) South East Asian Affairs 2004 (Singapore: Institute of South East Asian Studies, 2004)

- James Chin. “Autonomy: Politics in Sarawak” in Bridget Welsh (ed) Reflections: The Mahathir Years, (Washington DC: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2004) (ISBN 9790615 124871) pp 240–251

- Straumann, Lukas (2014) "Money Logging: On the Trail of the Asian Timber Mafia" Basel, Bergli Books

External links[edit]

| Media from Commons | |

| Source texts from Wikisource | |

| Textbooks from Wikibooks | |

| Travel guide from Wikivoyage | |

- Sarawak Government Portal

- Sarawak Tourism Board

- Tourism Malaysia - Sarawak

- Laws of Sarawak

- Sarawak Lonely Planet

- Audio slideshow: Sarawak, Malaysia- Exploring the enormous caves of Mulu with speleologist Andy Eavis. The Royal Geography Society's Hidden Journeys project.

|

South China Sea | South China Sea |  |

|

| South China Sea | ||||

|

||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||