| preceded by | ||||

|

||||

|

|||||||

|

|

|||||||

| succeeded by |

| Second Bulgarian Empire (1185 - 1422)from the Wikipedia | Read original article |

| Second Bulgarian Empire | |||||

| ц︢рьство блъгарское Второ българско царство |

|||||

|

|||||

|

Bulgaria under Ivan Asen II

|

|||||

| Capital | Tarnovo (1185 –1393) Vidin and Nikopol (1393–1396) |

||||

| Languages | Middle Bulgarian | ||||

| Religion | Orthodox Christianity | ||||

| Government | Monarchy | ||||

| Tsar (Emperor) | |||||

| - | 1185–1190 | Peter IV (first) | |||

| - | 1396–1422 | Constantine II (last) | |||

| Historical era | Middle Ages | ||||

| - | Reestablishment | 1185 | |||

| - | Fall under Ottoman rule | 1396 | |||

| Area | |||||

| - | 1205[1] | 248,000 km² (95,753 sq mi) | |||

| - | 1241[1] | 477,000 km² (184,171 sq mi) | |||

| - | 1350[1] | 137,000 km² (52,896 sq mi) | |||

| Today part of | |||||

The Second Bulgarian Empire (Bulgarian: Второ българско царство, Vtorо Bălgarskо Tsartsvo) was a medieval Bulgarian state which existed between 1185 and 1396 (or 1422).[2] A successor of the First Bulgarian Empire, it reached the peak of its power under Kaloyan and Ivan Asen II before gradually being conquered by the Ottomans in the late 14th and early 15th century. It was succeeded by the Principality and later Kingdom of Bulgaria in 1878.

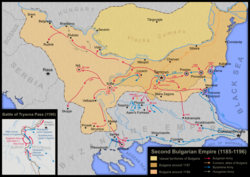

Until 1256, the Second Bulgarian Empire was the dominant power in the Balkans. The Byzantines were defeated in several major battles, and in 1205 the newly established Latin Empire was crushed in the Battle of Adrianople by Emperor Kaloyan. His nephew Ivan Asen II defeated the Despotate of Epiros and made Bulgaria a regional power once again. During his reign Bulgaria spread from the Adriatic to the Black Sea and the economy flourished. However, in the late 13th century the Empire declined under constant invasions of Mongols, Byzantines, Hungarians, and Serbs, as well as internal unrest and revolts. The 14th century brought temporary recovery and stability, but also saw the highest point of Balkan feudalism as central authorities gradually lost power in many regions, before Bulgaria was divided into three parts on the eve of the Ottoman invasion.

Despite strong Byzantine influence, the Bulgarian artists and architects created their own distinct style. In the 14th century, during the period known as the Second Golden Age of Bulgarian culture, literature and art flourished.[3] The capital city of Tarnovo, considered a "New Constantinople", became the country's main cultural hub, and the center of the Eastern Orthodox world for contemporary Bulgarians.[4] After the Ottoman conquest, many Bulgarian clerics and scholars emigrated to Serbia, Wallachia, Moldavia, and Russian principalities, where they introduced Bulgarian cultural achievements, books and hesychastic ideas.[5]

Contents

Nomenclature[edit]

The most frequently used name by contemporaries was Bulgaria, as the state called itself.[6] During Kaloyan's reign the state was sometimes known as being both of Bulgarians and Vlachs. Pope Innocent III[7] and other foreigners such as the Latin emperor Henry[8] mentioned the state as Bulgaria and the Bulgarian Empire in official letters.

In modern historiography the state is called the Second Bulgarian Empire, Second Bulgarian Tsardom or the Second Bulgarian Kingdom[9] in order to distinguish it from the First Bulgarian Empire. An alternative name (used in connection with the pre-mid 13th century period) is the Empire of Vlachs and Bulgars,[10] whose different variants include the Vlach–Bulgarian Empire, the Bulgarian–Wallachian Empire[11] or the Romanian–Bulgarian Empire, the last one was used exclusively in Romanian historiography.[12]

Background[edit]

In 1018, when the Byzantine emperor Basil II (r. 976–1025) conquered the First Bulgarian Empire he ruled it cautiously. The existing tax system,a[›] laws, and the power of low-ranking nobility remained unchanged until his death in 1025. The autocephalous Bulgarian Patriarchate was subordinated to the Ecumenical Patriarch in Constantinople and downgraded to an archbishopric centred in Ohrid, while retaining its autonomy and dioceses. Basil appointed the Bulgarian John I Debranin as its first archbishop, but all of his successors were Byzantines. The Bulgarian aristocracy and tsar's relatives were given various Byzantine titles and transferred to the Asian parts of the Empire.[13][14] Despite hardships, the Bulgarian language, literature and culture survived; surviving period texts refer to and idealise the Bulgarian empire.[15] The bulk of the newly conquered territories were included in the themes Bulgaria, Sirmium and Paristrion.

|

Part of

a series on the

|

|---|

| History of Bulgaria |

|

|

| Main category Bulgaria portal |

As the Byzantine Empire declined under Basil's successors, invasions of Pechenegs and rising taxes contributed to increasing discontent, which resulted in several major uprisings in 1040–1041, the 1070s, and the 1080s. The initial centre of the resistance was the theme of Bulgaria, in what is now Macedonia, where the massive Uprising of Peter Delyan (1040–1041) and the Uprising of Georgi Voiteh (1072) took place. Both were quelled with great difficulty by Byzantine authorities.[16] These were followed by rebellions in Paristrion and Thrace.[17] During the Comnenian Restoration, and the temporary stabilisation of the Byzantine Empire in the first half of the 12th century, the Bulgarians were pacified and no major rebellions took place until later in the century.

History[edit]

Liberation[edit]

The disastrous rule of the last Comnenian emperor Andronikos I (r. 1183–1185) worsened the situation of the Bulgarian peasantry and nobility. His successor Isaac II Angelos' first act was to impose an extra tax for his wedding.[18] In 1185, two aristocrat brothers from Tarnovo, Theodore and Asen, asked the emperor to be enlisted in the army and receive land, but Isaac II declined and slapped Asen across the face.[19] Upon their return to Tarnovo, the two brothers commissioned the construction of a church dedicated to Saint Demetrius of Salonica. They showed the populace a celebrated icon of the saint, whom they claimed had left Salonica to support the Bulgarian cause and called for a rebellion. That act had the desired effect on the religious population, which enthusiastically engaged in a rebellion against the Byzantines. Theodore, the elder brother, was crowned Emperor of Bulgaria under the name Peter IV, after the sainted Peter I (r.927–969).b[›][20] Almost all of Bulgaria to the north of the Balkan Mountains, the region known as Moesia, immediately joined the rebels, who also managed to secure the assistance of the Cumans, a Turkic tribe inhabiting lands north of the Danube river. The Cumans soon became an important part of the Bulgarian army, playing a major role in the successes that followed.[21][22] As soon as the rebellion broke out, Peter IV attempted to seize the old capital of Preslav but failed, and so declared Tarnovo to be new capital of the reborn Bulgaria.[23]

From Moesia, the Bulgarians launched attacks in northern Thrace while the Byzantine army was fighting with the Normans, who had attacked Byzantine possessions in the Western Balkans and had sacked Salonica, the Empire's second largest city. The Byzantines reacted in the early summer of 1186 when Isaac II organized a campaign to crush the rebellion before it spread further. The Bulgarians had secured the passes but the Byzantine army managed to find a way across the mountains due to a solar eclipse.[6][24] Once the Byzantines reached the plains, the rebels did not risk a confrontation with the larger and better organised force. Peter IV pretended that he was willing to submit, while Asen travelled to the north of the Danube to raise an army. Contented, the Byzantine emperor burned the Bulgarians' crops and returned to Constantinople. Soon after, Asen crossed back over the Danube with Cuman reinforcements, declaring that he would continue the struggle until all Bulgarian lands were liberated.[24] A new Byzantine army was assembled under the command of the emperor's uncle John Doukas Angelos, but as Isaac II feared he would be overthrown, Doukas was replaced by John Kantakouzenos, a blind man ineligible for the throne. Kantakouzenos' camp was attacked by the Bulgarians during the night, and lost a large number of soldiers.[25][26] In the summer of 1186, another army under the general Alexios Branas was sent in. However, instead of fighting the rebels, Branas turned to Constantinople to claim the throne for himself, but was murdered shortly afterwards.[27] Taking advantage of the chaos, the Bulgarians raided northern Thrace, looting the countryside before Byzantine forces could counter them. On one occasion, the two armies confronted each other near the fortress of Lardea in an indecisive battle; the Bulgarians managed to keep their plunder and retreat untroubled to the north of the Balkan mountains.[28]

In the late autumn of 1186, Isaac II launched his second campaign against Bulgaria, but his army was forced to spend the winter in Sofia, giving the Bulgarians time to prepare for the invasion. In the spring of the following year, the Byzantines besieged Lovech but could not seize it, and signed an armistice which de facto recognized Bulgarian independence.[28][29][30] In 1189, when the leader of the Third Crusade, emperor Frederick I Barbarossa was at the brink of war with the Byzantines, Asen and Peter IV offered him an army of 40,000 in return for official recognition, but relations between the Crusaders and the Byzantines eventually improved. In 1190, Isaac II headed another anti-Bulgarian campaign which ended in a catastrophic defeat at the Tryavna Pass. The emperor barely escaped with his life and the Imperial treasury, including the crown and the cross, were captured by the victorious Bulgarians.[31] After that major success, Asen was crowned emperor and became known as Ivan Asen I.[32] Peter IV, who voluntarily stepped down to make way for his more energetic brother, retained his title but the actual authority was now concentrated in the hands of Ivan Asen.[33]

The victory at the Tryavna Pass was followed by more Bulgarian successes in the next four years, as the focus of the war shifted thoroughly to the south of the Balkan mountains. Ivan Asen's strategy of swift campaigns striking in different locations paid off, and he soon took control of the important cities of Sofia and Niš to the south-west, clearing the way to Macedonia.[34] In 1194, the Byzantines gathered a huge force composed of the eastern and western armies, but suffered a devastating defeat in the Battle of Arcadiopolis. Unable to resist, Isaac II tried to ally with the Hungarian king Béla III and make a joint attack against Bulgaria, but was deposed and blinded by his brother Alexios III Angelos.[35] The Byzantines tried to negotiate peace, but Ivan Asen demanded the return of all Bulgarian lands and the war continued. In 1196, the Byzantine army was once again defeated at Serres, deep to the south. Upon his return to Tarnovo, Ivan Asen was murdered by his cousin Ivanko in a plot inspired by Constantinople.[36] Peter IV besieged Tarnovo, and Ivanko fled to the Byzantine Empire where he was made governor of Philippopolis. Peter IV himself was murdered less that a year after his brother's demise.[37]

Rise[edit]

The throne was succeeded by Asen and Peter IV's youngest brother, Kaloyan. An ambitious and ruthless ruler, he desired international recognition and to finish the liberation of Bulgaria. Kaloyan also wanted revenge against the Byzantines for emperor Samuel's 14,000 blinded soldiers, and called himself Romanoktonos (Roman-slayer) as Basil II was called Bulgaroktonos (Bulgar-slayer).[38] He did not hesitate to ally with his brother's murderer Ivanko. The Byzantines managed to kill Ivanko, but the Bulgarians took the city of Constantia. In 1201, Kaloyan captured Varna, the last Byzantine stronghold in Moesia, which was defended by a large garrison. Despite the fact that the city fell in Easter, Kaloyan ordered every Byzantine to be thrown in the moat.[39] He then negotiated peace with Byzantines, securing Bulgarian gains in early 1202.[40] While the Bulgarians were occupied in the south, the Hungarian king Andrew II and his Serbian vassal Vukan had annexed Belgrade, Braničevo, and Niš, but after negotiating peace, Kaloyan turned his attention to the north-west. In 1203, the Bulgarians pushed the Serbs out of Niš, defeated the Hungarian army in several battles along the valley of the Morava river, and regained their lost lands.[40]

Kaloyan was aware that the Byzantines would never recognize his imperial title and began negotiations with Pope Innocent III. He based the claims on his predecessors in the First Bulgarian Empire: Simeon I, Peter I and Samuel.[41] The Pope was only willing to recognise him as King on the condition that the Bulgarian Church would submit to Rome, and after long negotiations in which both acted diplomatically, but without changing their positions, Kaloyan was crowned King in the autumn of 1204 with archbishop Basil proclaimed Primate. Kaloyan had no intention to submit to that decision and sent the Pope a letter, expressing his gratitude for the Imperial title he had received and the elevation of the Bulgarian Church to a Patriarchate, and eventually the Papacy tacitly accepted the Bulgarian position regarding the Imperial title.[42][43][44] The union between Bulgaria and Rome remained strictly official, as the Bulgarians did not change their Orthodox rites and traditions.[44]

Several months before Kaloyan's coronation, the leaders of the Fourth Crusade turned on the Byzantine Empire and captured Constantinople, creating the Latin Empire. The Bulgarians tried to establish friendly relations with the Latins but were rebuffed, and the Latins claimed their lands despite Papal recognition. Facing a common enemy, Kaloyan and the Byzantine aristocracy in Thrace made an alliance and the latter promised they would accept Kaloyan as their emperor.[45][46] The decisive battle between the Bulgarian army and the Crusaders took place on 14 April 1205 at Adrianople, and resulted in a crushing defeat for the Latins and the capture of their emperor Baldwin I. The battle was a blow to the newly founded Latin Empire, which descended into chaos.[47][48] After the victory, the Bulgarians retook most of Thrace, including the important city of Philippopolis. The unexpected Bulgarian successes caused the Byzantine nobility to plot against Kaloyan and ally themselves with the Latins.[49] The plot in Tarnovo was quickly discovered, and Kaloyan retaliated with brutal reprisals against the Byzantines in Thrace. The campaign against the Latins also continued, and in 1206, the Bulgarians scored another major victory in the battle of Rusion, conquering a number of towns in Eastern Thrace. In the following year, the King of Salonica Boniface I was killed in battle, but Kaloyan was murdered before he could begin the assault on the capital.[50]

Kaloyan was succeeded by his cousin Boril, who tried to pursue his predecessor's policies, but did not have his capability. His army was defeated by the Latins at Philippopolis and lost most of the gains Kaloyan had achieved. Boril also failed to maintain the integrity of the empire; his brother Strez took most of Macedonia for himself, Alexius Slav broke off in the Rhodopes and in return for help suppressing a major rebellion in 1211, Boril was forced to cede Belgrade and Braničevo to Hungary. A campaign against Serbia in 1214 ended in another failure.[51][52]

As a result of the growing discontent with his policy, Boril was overthrown in 1218 by Ivan Asen II, son of Ivan Asen I, who had lived in exile in the Russian principalities after Kaloyan's death.[53] After his coronation, Ivan Asen II arranged a wedding with Anna Maria, daughter of the Hungarian king Andrew II, and received the lost Belgrade and Braničevo as a dowry. He then signed an alliance with Theodore Komnenos, the ruler of the most powerful Byzantine successor state, the Despotate of Epirus. With his northern border secured by the treaty, Theodore Komnenos managed to conquer Salonica, greatly reducing the size of the Latin Empire, and in 1225 proclaimed himself emperor.[54] By 1228, the situation became desperate for the Latins, and they entered in negotiations with Bulgaria, promising a marriage between the underage emperor Baldwin II and the daughter of Ivan Asen II, Helena. This marriage would have made the Bulgarian emperor a regent in Constantinople, but in the meantime they offered the regency to the French nobleman John of Brienne.[53] Concerned with the actions of the Bulgarians, while marching on Constantinople in 1230, Theodore Komnenos invaded Bulgaria with a huge army. Surprised, Ivan Asen II gathered a small force and moved to the south to engage the enemy. Instead of a banner, he used the peace treaty with Theodore's oath and seal stuck on his spear and won a major victory in the Battle of Klokotnitsa. Theodore Komnenos was captured along with his whole court and most of the surviving troops.[55][56][57] Ivan Asen II released all ordinary soldiers and marched on the Epyrote–controlled territories, where all cities and towns surrendered and recognized his rule, from Adrianople to Durazzo on the Adriatic Sea. Theodore's brother Michael II Komnenos Doukas was allowed to rule in Salonica over the southern areas of the despotate as a Bulgarian vassal.[58][59] It is possible that Serbia accepted Bulgarian suzerainty at that time to counter the threat from Catholic Hungary.[60]

| “ | I waged war in Romaniac[›], defeated the Greek army, and captured the Lord Emperor Theodore Comnenus himself and all his boyars. And I occupied all the land from Adrianople to Durazzo, Greek, Serbia and Albanian alike. The Franksc[›] hold only the cities in the vicinity of Constantinople itself. But even they [these cities] are under the authority of my empire since they have no other emperor but me, and only thanks to me do they survive, for thus God has decreed. —Tarnovo inscription of Ivan Asen II in the Church of the Holy Forty Martyrs on the aftermath of the battle of Klokotnitsa.[61] |

” |

In 1231, when John of Brienne arrived in Constantinople, Ivan Asen II allied with the Nicaean Empire against the Latins. After the Nicaeans recognized the Bulgarian Patriarchate in 1235, Ivan Asen II broke his union with the Papacy. The joint campaign against the Latins was successful, but they failed to capture Constantinople. With John of Brienne's death two years later, Ivan Asen II, who could have again become a regent of Baldwin II, decided to end his cooperation with Nicaea.[62] His decision was further based on the assumption that after an allied success, Constantinople would again have turned into the centre of a restored Byzantine Empire, with the Nicaean dynasty as a ruling house.[63] The Bulgarian–Latin cooperation was short–lived and Ivan Asen II remained in peace with his southern neighbours until the end of his reign. Shortly before his death in 1241, Ivan Asen II defeated part of the Mongol army returning to the east after a devastating attack on Poland and Hungary.[64]

Decline[edit]

Ivan Asen II was succeeded by his infant son Kaliman I. Despite the initial success against the Mongols, the regency of the new emperor decided to avoid further raids and chose to pay them tribute instead.[65] The lack of a strong monarch and increasing rivalriess among the nobility caused Bulgaria to rpaidly decline, while its main rival Nicaea avoided Mongol raids, gaining power in the Balkans.[66] After the death of 12-year-old Kaliman I in 1246, the throne was succeeded by several short–reigned rulers. The weakness of the new government was exposed when the Nicaean army conquered huge areas in southern Thrace, the Rhodopes, and Macedonia, including Adrianople, Tsepina, Stanimaka, Melnik, Serres, Skopje, and Ohrid, meeting little resistance. The Hungarians also exploited Bulgarian weakness, occupying Belgrade and Braničevo.[67][68] It was as late as 1253 when the Bulgarians reacted, invading Serbia and regaining the Rhodopes the following year. However, Michael II Asen's indecisiveness allowed the Nicaeans to regain all of their lost territory, with the exception of Tsepina. In 1255 the Bulgarians quickly regained Macedonia, whose Bulgarian population preferred the rule of Tarnovo to that of the Nicaeans.[69] All gains were, however, definitely lost in 1256, after the Bulgarian representative Rostislav Mikhailovich betrayed his cause and reaffirmed Nicaean control over the disputed areas.[69][70] That major setback cost the emperor's life, and led to a period of instability and civil war between several claimants to the throne, until 1257 when the boyar of Skopje Constantine Tikh emerged as a victor.[71]

The new emperor had to deal with multiple foreign threats. In 1257 the Latins attacked and seized Messembria but could not hold the town. More serious was the situation to the north–west, where the Hungarians supported Rostislav, the self–proclaimed Emperor of Bulgaria in Vidin. In 1260, Constantine Tikh recovered Vidin and occupied the Severin Banat, but in the next year a Hungarian counter–attack forced the Bulgarians to retreat to Tarnovo, restoring Vidin to Rostislav.[72] The city was soon controlled by the Bulgarian noble Jacob Svetoslav, but by 1266 he too styled himself emperor.[73] The restoration of the Byzantine Empire under the ambitious Michael VIII Palaiologos further worsed Bulgaria's stiuation. A major Byzantine invasion in 1263 led to the loss of the coastal towns Messembria and Anchialus, and several cities in Thrace including Philippopolis.[74] Unable to effectively resist, Constantine Tikh organized a joint Bulgarian–Mongol campaign, but after ravaging Thrace the Mongols returned north of the Danube.[75] The emperor became crippled after a hunting accident in the early 1260s, and fell under the influence of his wife Maria Palaiologina whose constant intrigues fuelled divisions among the nobility.[76]

Constant Mongol raids, economic difficulties and the emperor's illness led to a massive popular uprising in the north-east in 1277. The rebel army, led by the swineherd Ivaylo, defeated the Mongols twice, greatly boosting their popularity. Ivaylo then turned on and defeated the regular army under the command of Constantine Tikh. He personally killed the emperor, claiming that the latter did nothing to defend his honor.[77][78] Fearing that a revolt might rise up in Byzantium, and willing to exploit the situation, the emperor Michael VIII sent an army headed by a Bulgarian pretender to the throne Ivan Asen III, but the rebels reached Tarnovo first. Constantine Tikh's widow Maria married Ivaylo, and he was proclaimed emperor. After the Byzantines failed, Michael VIII turned to the Mongols, who invaded Dobrudzha and defeated Ivaylo's army, forcing him to retreat to Drastar, where he withstood a three–month siege.[79][80][81] After his defeat, Ivaylo was betrayed by the Bulgarian nobility, who opened the gates of Tarnovo to Ivan Asen III. In early 1279, Ivaylo broke off the siege at Drastar and besieged the capital. The Byzantines sent a 10,000–strong army to relieve Ivan Asen III, but suffered defeat at Ivaylo's hands in the battle of Devina. Another army of 5,000 had a similar fate, forcing Ivan Asen III to flee.[82] Ivaylo's situation did not improve, however – after two years of constant warfare his support was diminished, the Mongols were not decisively defeated and the nobility remained hostile. By the end of 1280 Ivaylo sought refuge with his former enemies, the Mongols, who under Byzantine influence killed him.[83] The nobility chose the powerful noble George I Terter, ruler of Cherven, as emperor. Though he managed to hold the throne for twelve years, his reign brought even stronger Mongol influence and the loss of most of the remaining lands in Thrace to the Byzantines. That period of instability and uncertainty continued until 1300, when for a few months the Mongol Chaka ruled in Tarnovo.[84]

Temporary stabilisation[edit]

In 1300 Theodore Svetoslav, George I's eldest son, took advantage of a civil war in the Golden Horde, overthrew Chaka and presented his head to the Mongol khan Toqta. That move not only brought the end of Mongol interference in Bulgarian domestic affairs but also secured Southern Bessarabia as far as Bolgrad to Bulgaria.[85] The new emperor began to rebuild the country's shattered economy, subdued many of the semi–independent nobles and executed those he held responsible for assisting the Mongols as traitors, including Patriarch Joakim III.[86][87][88] The Byzantines, interested in Bulgaria's continuous instability, supported two pretenders with their armies, Michael and Radoslav, but were defeated by Theodore Svetoslav's uncle Aldimir, the despot of Kran. Between 1303 and 1304 the Bulgarians launched several campaigns and retook many towns in north–eastern Thrace. The Byzantines tried to counter the Bulgarian advance but suffered a major defeat in the battle of Skafida. Unable to change the status quo, they were forced to make peace with Bulgaria in 1307, acknowledging Bulgarian gains.[89][90] Theodore Svetoslav spent the rest of his reign in peace with his neighbours. He maintained cordial relations with Serbia and in 1318 its king Stephen Milutin paid a visit to Tarnovo. The years of peace brought economic prosperity, boosted commerce and Bulgaria became a major exporter of agricultural commodities, especially wheat.[91][92]

During the early 1320s, tensions between Bulgaria and the Byzantines rose, as the latter descended into a civil war and the new emperor George II Terter seized Philippopolis. The Byzantines were able to recover the city, as well as other towns in northern Thrace, in the confusion that followed George II's unexpected death in 1322 without leaving a successor.[93] The energetic despot of Vidin, Michael Shishman, was elected emperor the next year and immediately turned on the Byzantine emperor Andronikos III Palaiologos, regaining the lost lands.[94] In the autumn of 1324 the two monarchs signed a peace treaty, strengthened by a marriage between the Bulgarian ruler and Theodora Palaiologina. Michael Shishman divorced his Serbian wife Anna Neda which deteriorated relations with Serbia. That change of the political course was explained with the rapid growth of Serbian power and its penetration into Macedonia.[95][96] The Bulgarians and the Byzantines agreed to a joint campaign against Serbia, but it took five years until the differences and tensions between Bulgaria and Byzantium were finally overcome .[97] Michael Shishman gathered 15,000 troops and invaded Serbia. He engaged the Serbian king Stephen Dečanski, who commanded an approximately equal force, near the border town of Velbazhd. The two rulers, both expecting reinforcements, agreed to a one–day truce but when a Catalan detachment under the king's son Stephen Dušan arrived, the Serbs broke their word and in the ensuing battle the Bulgarians were defeated and their emperor perished.[98] Despite their victory, the Serbs did not risk an invasion of Bulgaria and the two sides agreed to a peace. As a result, Ivan Stephen, the eldest son of the deceased emperor by his Serbian wife, succeeded him in Tarnovo and was deposed after a brief rule.[99] Bulgaria did not lose territoryd[›] but could not stop the Serbian expansion in Macedonia.[100]

After the disaster at Velbazhd, the Byzantines attacked Bulgaria, seizing a number of towns and castles in northern Thrace. Their success ended in 1332, when the new emperor Ivan Alexander defeated them in the battle of Rusokastro, recovering the lost territories.[100][101] In 1344 the Bulgarians entered the Byzantine civil war of 1341–1347 on the side of John V Palaiologos against John VI Kantakouzenos, acquiring nine towns along the Maritsa river and in the Rhodope Mountains, including Philippopolis. That acquisition marked the last significant territorial expansion of medieval Bulgaria, but also led to the first attacks on Bulgarian soil by the Ottoman Turks, who were allied with Kantakouzenos.[102]

Fall[edit]

The attempts of Ivan Alexander to fight off the Ottomans in the late 1340s and early 1350s failed after two defeats, which possibly claimed the life of his eldest son and successor Michael Asen IV and his second son Ivan Asen IV.[103] The emperor's relations with his other son Ivan Sratsimir, who had been installed as the ruler of Vidin, deteriorated after, in 1349, Ivan Alexander divorced his wife to marry Sarah-Theodora, a converted Jew. When their child Ivan Shishman was designated as an heir to the throne, Ivan Sratsimir proclaimed independence.[104] In 1366, Ivan Alexander refused to grant passage to the Byzantine emperor John V Palaiologos, and the troops of the Savoyard crusade attacked the Bulgarian Black Sea coast. They seized Sozopolis, Messembria, Anchialus, and Emona with heavy casualties and unsuccessfully laid siege to Varna. The Bulgarians eventually granted passage to John V, but the lost towns were handed over to the Byzantines.[105] To the north-west the Hungarians attacked and occupied Vidin in 1365. Ivan Alexander managed to reconquer his province four years later, allied with his de jure vassals Vladislav I of Wallachia and Dobrotitsa.[106][107] The death of Ivan Alexander in 1371 left the country irrevocably divided between Ivan Shishman in Tarnovo, Ivan Sratsimir in Vidin, and Dobrotitsa in Karvuna. The 14th century German traveller Johann Schiltberger described these lands as follows:[108]

| “ | I was in three regions, and all three were called Bulgaria. The first Bulgaria extends there, where you pass from Hungary through the Iron Gate. Its capital is called Vidin. The other Bulgaria lies opposite Wallachia, and its capital is called Tarnovo. The third Bulgaria is there, where the Danube flows into the sea. Its capital is called Kaliakra. | ” |

On 26 September 1371, the Ottomans defeated a large Christian army led by the Serbian brothers Vukašin Mrnjavčević and Jovan Uglješa in the Battle of Chernomen. They immediately turned on Bulgaria and conquered northern Thrace, the Rhodopes, Kostenets, Ihtiman, and Samokov, effectively limiting the authority of Ivan Shishman to the lands to the north of the Balkan mountains and the Valley of Sofia.[109] Unable to resist, the Bulgarian monarch was forced to become an Ottoman vassal, and in return managed to recover some of the lost towns and secure ten years of uneasy peace.[109][110] The Ottoman raids renewed in the early 1380s, and culminated with the fall of Sofia.[111] Simultaneously, Ivan Shishman had been engaged in war against Wallachia since 1384. According to the Anonymous Bulgarian Chronicle he killed the Wallachian voivode Dan I of Wallachia in September 1386.[112] He also maintained uneasy relations with Ivan Sratsimir, who had broken his last ties with Tarnovo in 1371, and had separated the dioceses of Vidin from the Tarnovo Patriarchate.[113] The two brothers did not cooperate to fight off the Ottoman invasion. Historians like Konstantin Jireček suggest that they bitterly conflicted over Sofia.[114] Despite his vassal obligation to support the Ottomans with troops during their campaigns, Ivan Shishman never assisted them. Instead, he used every opportunity to participate in Christian coalitions with the Serbs and the Hungarians, provoking massive Ottoman invasions in 1388 and 1393. Despite strong resistance, the Ottomans seized a number of important towns and fortresses in 1388, and five year later captured Tarnovo after a three–month siege.[115][116] Ivan Shishman perished in 1395 when the Ottomans, led by Bayezid I, took his last fortress Nikopol.[117] In 1396 Ivan Sratsimir joined the Crusade of the Hungarian king Sigismund but after the Christian army was defeated in the battle of Nicopolis the Ottomans immediately marched on Vidin and seized it, bringing the end to the medieval Bulgarian state.[118][119] Resistance continued under Constantine and Fruzhin until 1422. The former was referred to by king Sigismund as the "distinguished Constantine, glorious Emperor of Bulgaria".[120][121]

Administration, territorial division, society[edit]

The Second Bulgarian Empire was a hereditary monarchye[›] ruled by a Tsar – the Bulgarian word for Emperor that originated in the 10th century during the First Bulgarian Empire. The monarchs of Bulgaria styled themselves as "In Christ the Lord Faithful Emperor and Autocrat of all Bulgarians" or similar variations, sometimes including "...and Romans, Greeks, or Vlachs".[122] The term all Bulgarians was added in the 14th century following the loss of many Bulgarian-populated territories and signified that the monarch in Tarnovo was the emperor of the whole Bulgarian people, even those who lived beyond the political borders of the country.[122]

The Emperor had the supreme power in both secular and religious affairs in a system known as Autocracy and his personal abilities played an important role in the country's well-being.[123] When the monarch was infant the government was headed by a regency which included the mother-empress, the Patriarch and senior members of the ruling dynasty.[124] As the processes of feudal fragmentation accelerated in the 14th century it became customary the monarch’s sons to receive imperial titles during their fathers' lifetime and were styled co-rulers or junior emperors.[125]

Unlike the First Empire, the administration during the Second Bulgarian Empire was heavily influenced by the Byzantine system of administration. Most of the titles of the nobility, the court and the administration were directly adopted from their Byzantine counterparts in Byzantine Greek or were translated into Bulgarian language. There were some differences in the ranking systems between the two countries but there are few surviving sources about the precise obligations, insignia or ceremonial of the medieval Bulgarian administration.[126] The Bolyar Council included the greater bolyars and the Patriarch and discussed issues about the external and internal policy such as declaration of war, formation of alliance or signing peace.[127] The highest-ranking administrative officials were the great logothete who had the functions of a first minister, and the protovestiarios who was responsible for the treasury and finance.[127] High court titles such as despot and sebastokrator were awarded to the relatives of the emperor but were not related with strict administrative functions.[128]

The capital was Tarnovo which was also the centre of its own administrative unit under the direct authority of the emperor.[129] Bulgaria was divided into provinces whose number varied with the territorial evolution of the country. In the surviving primary sourced the provinces were called with the Byzantine term hora or the Bulgarian zemya (земя), strana (страна) and oblast (област), usually named after the main city.[130][131] The provincial governors were called duke or kefalia (both from Byzantine dux and kephale) and were directly appointed by the emperor. The provinces were further divided into katepanika (sing. katepanikon, from the Byzantine katepanikion) which were ruled by katepans who were subordinated to the dukes.[132] During the reign of Ivan Asen II (1218–1241) the provinces included Belgrade, Braničevo, Vidin, Tarnovo, Zagore, Preslav, Karvuna, Kran, Boruy, Adrianople, Dimotika, Skopje, Prilep, Devol and Albania.[132]

The society was divided into three classes – clergy, nobility and peasantry. The second class included the aristocracy – the bolyars, whose origin was the older Bulgarian boilas from the First Empire, the judges and the "whole army".[133] The bolyars were further divided into greater and lesser bolyars. The former possessed large estates which at times included tens and even hundreds of villages, and held high administrative and military posts.[134] The peasants formed the bulk of the third class and were subordinated either under the central authorities or under local feudal lords. With time the number of the latter increased as a result of the process of feudalisation of Bulgaria.[135] The main groups of peasants were paritsi and otrotsi. Both could possess land but while the paritsi could inherit property the latter could not, as it was provided by the feudal.[136]

Military[edit]

The commander-in-chief of the army was the emperor and the second-in-command was the velik (great) voivoda. The detachments of the army were led by a voivoda. The strator was responsible for the defence of certain regions and the recruitment of soldiers.

In the late 12th century the army numbered 40,000 men-at-arms.[33] The country was able to mobilise around 100,000 men in the first decade of the 13th century (Kaloyan reportedly offered the leader of the Fourth Crusade Baldwin I 100,000 soldiers to help him take Constantinople).[137] By the end of the century the military declined and the army was reduced to less than 10,000 men — it was recorded that Ivaylo defeated two Byzantine armies of 5,000 and 10,000 men, and that his troops were outnumbered in both cases.[82] Military strength increased with the political stabilisation of Bulgaria in the first half of the 14th century and the army numbered 11,000–15,000 troops in the 1330s.[138] The military was well supplied with siege equipment, including battering rams, siege towers and catapults.

The Bulgarian army employed various military tactics relying both on the experience of the soldiers and the peculiarities of the terrain. The Balkan mountains played a significant role in the military strategy and facilitated the country's defence against the strong Byzantine army. During war the Bulgarians would send light cavalry to devastate the enemy lands on a broad front pillaging villages and small towns, burning the crops and taking people and cattle. The Bulgarian army was very mobile — for instance prior to the battle of Klokotnitsa for four days it covered a distance three times longer than the Epirote army for a week; in 1332 it covered 230 km for five days.[138]

| “ | Inside the fortress [Sofia] there is a large and elite army, its soldiers are heavily built, moustached and look war-hardened, but are used to consume wine and rakia - in a word, jolly fellows.[139] | ” |

| —Ottoman commander Lala Shahin on the garrison of Sofia. |

||

Bulgaria maintained extensive lines of fortresses to protect the country, with the capital Tarnovo in the centre: to the north along both banks of the Danube river; to the south three lines, the first along the Balkan mountains, the second along Vitosha, northern Rhodope mountains and Sakar mountain, the third along the valley of the river Arda; to the west along the valley of the river South Morava.[140]

During the Second Empire, foreign and mercenary soldiers became an important part of the Bulgarian army and its tactics. Since the very beginning of the rebellion of Asen and Peter, the light and mobile Cuman cavalry was effectively used against the Byzantines and later the Crusaders. Fourteen thousand of them were used by Kaloyan in the battle of Adrianople.[137] The Cuman leaders entered the ranks of the Bulgarian nobility, and some of them received high military or administrative posts in the state.[141] In the 14th century the Bulgarian army increasingly relied on foreign mercenaries, which included Western knights, Mongols, Ossetians or came from vassal Wallachia. Both Michael III Shishman and Ivan Alexander had a 3,000–strong Mongol cavalry detachment in their armies.[138] In the 1350s, emperor Ivan Alexander even hired Ottoman bands, as did the Byzantine Emperor. Russians were also hired as mercenaries.[142]

Economy[edit]

The economy of the Second Bulgarian Empire was based on agriculture, mining, traditional crafts and trade. Agriculture and livestock breeding remained the backbone of the Bulgarian economy between the 12th and the 14th centuries. Moesia, Zagore and Dobrudzha were known for the rich harvests of grain, including high quality wheat.[143] Production of wheat, barley and millet was also developed in most regions of Thrace.[144] The main wine–producing areas along with Thrace were the Black Sea coast and the valleys of the Struma and Vardar rivers in Macedonia.[145] The importance of vegetables, orchards and grapes grew since the beginning of the 13th century.[146] The existence of large forests and pastures was favourable for livestock breeding, mainly in the mountainous and semi–mountainous regions of the country. Livestock included sheep, cattle, horses and oxen.[147] Sericulture and especially apiculture were well developed. The honey and wax from Zagore were the best known in the Byzantine markets and the highly praised.[148] The forests were divided into two types: woods for cutting (бранища) and fenced forests (забели) in which cutting was banned.[149]

The increase of the number of towns gave strong impetus to handicrafts, metallurgy and mining. Processing of crops was traditional, production included bread, cheese, butter, wine; salt was extracted from the lagoon near Anchialus.[150] Leathermaking, shoemaking, carpentry, weaving were prominent. Varna was renown for the processing of fox fur which was used for luxurious clothes.[151] Western European sources claim that there was abundance of silk in Bulgaria. The Picardian knight Robert de Clari testified that in the dowry of the Bulgarian princess Maria "...there was not a single horse that was not covered in red silk fabric, which was so long that dragged for seven or eight steps after each horse. And despite they travelled through mud and bad roads, none of the silk fabrics was torn — everything was preserved in grace and nobility."[152] There were blacksmiths, ironmongers and engineers who developed catapults, battering-rams and other siege equipment which were extensively used in the beginning of the 13th century.[153] Metalworking was developed in western Bulgaria — Chiprovtsi, Velbazhd, Sofia, as well in the capital Tarnovo and Messembria to the east.[154]

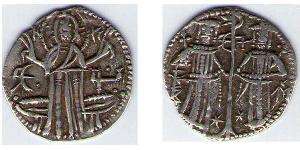

Monetary circulation and minting steadily increased throughout that period, reaching their climax during the reign of Ivan Alexander (r. 1331–1371). Along with his recognition by the Pope, emperor Kaloyan (r. 1197–1207) acquired the right to mint coins. Well–organised mints and engraving workshops were set up in the mid 13th century, producing copper, billon and silver coinage.[155][156] The reform was initiated by Constantine Tikh Asen (r. 1257–1277) and led to stabilisation of the monetary market in Bulgaria. The Uprising of Ivaylo and the pillage raids of the Mongols in the last two decades of the 13th century had a negative impact on the coinage, resulting in a tenfold decrease of the minting activities.[157] With the stabilisation of the empire since 1300 the Bulgarian monarchs issued an increased number of coins, including silver ones but were able to secure the market with domestic coins after the 1330s.[158] The erosion of the central authorities on the eve of the Ottoman invasion gave rise to primitive, anonymous and crude coins, forged by counterfeiters.[159] Along with the Bulgarian coinage, coins from the Byzantine Empire, Latin Empire, Venice, Serbia, the Golden Horde and the various small Balkan principalities were widely used. Due to the increase of production there was a tendency towards limitation of the foreign coins by the second half of the 14th century.[160] Coins were minted by some independent or semi–independent Bulgarian lords, such as Jacob Svetoslav and Dobrotitsa.[161]

Religion[edit]

Religious policy[edit]

Following the liberation of the country, the restoration of the Bulgarian Patriarchate became the priority of the Bulgarian foreign policy along with the recognition of the imperial title of the monarch. The continuous state of war against the Byzantine empire urged the Bulgarian rulers to turn to the Papacy. In his correspondence with Pope Innocent III Kaloyan (r. 1197–1207) demanded imperial title and a Patriarchate basing his claims on the heritage of the First Bulgarian Empire and promised in return to accept Papal suzerainty over the Bulgarian Church.[162][163] The union between Bulgaria and Rome was formalised on 7 October 1205 when Kaloyan was crowned King by a papal legate and the Archbishop of Tarnovo Basil was proclaimed Primate. In a letter to the Pope, however, Basil styled himself a Patriarch against which Innocent III did not argue.[42][164] Just like Boris I (r. 852–889) three centuries earlier Kaloyan pursued strictly political agenda in his negotiations with the Papacy without sincere intentions to convert to Roman Catholicism. The union with Rome lasted until 1235 and did not have any impact on the Bulgarian church which continued its practices along the Eastern Orthodox canons and rites.[44]

The ambition of Bulgaria to become the religious centre of the Orthodox world had a prominent place in the state doctrine of the Second Empire. After the fall of Constantinople to the knights of the Fourth Crusade in 1204 the capital Tarnovo became for a time main centre of Orthodoxy.[165] The Bulgarian emperors were zealously collecting relics of Christian saints to boost the prestige of their capital.[166] The official recognition of the restored Bulgarian Patriarchate in 1235 at the Council of Lampsacus was a major step in that direction and gave rise to the concept of Tarnovo as a "Second Constantinople".[167] The Patriarchate vigorously opposed the papal initiative to reunite the Orthodox Church with Rome and criticised the Patriarchate of Constantinople and the Byzantine emperor for their apparent willingness to make concessions at the Second Council of Lyon in 1272–1274. Patriarch Ignatius was called "pillar of Orthodoxy".[168] Envoys were sent to the Patriarch of Jerusalem to negotiate an anti-Byzantine alliance which was to include the other two Eastern Patriarchs but the mission did not bring any results.[169][170]

The disputes with the Patriarchate of Constantinople over the legitimacy of the Bulgarian Patriarchate intensified in the 14th century after in 1355 the Ecumenical patriarch Callistus I tried to assert his supremacy over the Bulgarian church and claiming that under the provisions of the Council of Lampsacus it remained subordinated and had to pay annual tribute to Constantinople. These claims, however, were not supported by any authentic documents and were ignored by the Bulgarian religious authorities.[171]

The structure of the Bulgarian Patriarchate followed the traditions of the First Empire. The head of the Church was the Patriarch who was a member of the State Council (Sinklit) and was at times a regent.[172] The patriarch was assisted by a Synod which included the bishops, high–ranking clerics and sometimes representatives of the secular authorities. The Bulgarian Church followed strictly the official state policy – the Patriarch Joakim III was executed for treason because of suspected links with the Mongols.[172] The territorial extend of the Bulgarian Patriarchate varied according to the territorial changes. At its height under the reign of Ivan Asen II (r. 1218–1241) it consisted of 14 dioceses – Preslav, Cherven, Lovech, Sofia, Ovech, Drastar, Vidin, Serres, Philippi, Messembria, Braničevo, Belgrade, Niš and Velbazhd, as well as the sees of Tarnovo and Ohrid.[173][172]

Hesychasm[edit]

Hesychasm (from Greek "stillness, rest, quiet, silence") is an eremitic tradition of prayer in the Eastern Orthodox Church which flourished in the Balkans during the 14th century. A mystical movement, Hesychasm preached a technique of mental prayer which when repeated with proper breathing might enable one to see the divine light.[174] Emperor Ivan Alexander (r. 1331–1371) was deeply impressed by the practice of Hesychasm and became a patron of Hesychastic monks. In 1335 he gave refuge to Gregory of Sinai and provided funds for the construction of a monastery near Paroria, Strandzha mountains in the south-east of the country which attracted clerics from Bulgaria, Byzantium and Serbia.[175] Hesychasm established itself as the dominant ideology of the Bulgarian Orthodox Church with the work of the disciple of Gregory of Sinai Theodosius of Tarnovo who translated his writing in Bulgarian and reached apogee during the tenure of the last medieval Bulgarian patriarch Euthymius of Tarnovo (1375–1394). Theodosius founded the Kilifarevo Monastery near the capital Tarnovo which became the new Hesychastic and literary centre of the country.[175][176] The Hesychastic intellectuals maintained regular connections among each other regardless of their nationality which had a significant impact on the cultural and religious exchange in the Balkans.

Bogomilism and other heresies[edit]

Bogomilism was a Gnostic dualistic sect founded in the 10th century in the First Bulgarian Empire[177] which subsequently spread all over the Balkans and flourished after the fall of Bulgaria under Byzantine rule. Considered heretics by the Eastern Orthodox Church, the Bogomils preached among others civil disobedience[177] which was particularly alarming for the state authorities.

Bogomilism saw a major resurge in Bulgaria as a result of the military and political setbacks during the reign of Boril (r. 1207–1218). The emperor took swift and decisive measures to suppress the Bogomils and on 11 February 1211 personally presided over the first anti-Bogomil synod in Bulgaria which was held in the capital Tarnovo.[178][179][180] Not surprisingly, during the discussions the Bogomils were exposed and those who did not return to Orthodoxy were condemned to exile. Despite the existing union with the Roman Catholic Church the synod followed strictly the canons of the Orthodox church and in the specially dedicated Book of Boril the monarch was described as "Orthodox emperor" and the Synod of Tarnovo was added to the list of Orthodox synods.[181] As a result of the actions of Boril the influence of the Bogomils was greatly diminished but not completely eradicated.

Many heretic movements established themselves in Bulgaria in the 14th century, including Adamites and Barlaamism which were brought by exiles from the Byzantine Empire.[182] These movements, along with the Bogomilism and Judaism, were condemned on the Council of Tarnovo in 1360 which was attended by the imperial family, the patriarch and many nobles and clerics. There are no sources about the existence of Bogomils in Bulgaria after 1360 which suggests that the sect had already been weakened and had few followers.[183] Persecution of the remaining Adamites and Barlaamists continued on a smaller scale headed by Theodosius of Tarnovo and patriarch Euthymius.[184]

Culture[edit]

The Second Bulgarian Empire was a centre of a thriving culture reaching its apogee in the mid and late 14th century during the reign of Ivan Alexander (r. 1331–1371).[184][185] This period saw a resurgence of Bulgarian architecture, arts and literature which spread beyond the borders of Bulgaria into Serbia, Wallachia, Moldavia and the Russian principalities, and had impact on Slavic culture in general.[186][187] In turn, Bulgaria was influenced by the contemporary Byzantine cultural trends.[187] The main cultural and spiritual centre was the capital Tarnovo which grew as a "Second Constantinople" ("Third Rome").[167] The city was called by the Bulgarian contemporaries "Tsarevgrad Tarnov", the Imperial city of Tarnovo, after the Bulgarian name of Constantinople – Tsarigrad.[188] Other important cultural hubs included Vidin, Sofia, Messembria and a large number of monasteries throughout the country.

Architecture[edit]

The network of cities in the Second Bulgarian Empire grew in the 13th and 14th centuries with numerous new urban centres rising to prominence. The cities were usually constructed in locations which were difficult to access and generally consisted of an inner and outer town. The nobility lived in the inner town which included the citadel, while most citizens inhabited the outer town. There were separate neighbourhoods for the nobility, the craftsmen, the merchants and the foreigners.[189][190] The capital Tarnovo had three fortified hills — Tsarevets, Trapezitsa and Momina Krepost, built along the meanders of the Yantra river, and several neighbourhoods along the banks of the river including separate quarters for Western Europeans and Jews.[191]

Fortresses were built on hills and plateaus — the Byzantine historian Niketas Choniates noted that the Bulgarian castles in the Balkan Mountains were situated "at heights above the clouds".[192] They were constructed with crushed stones welded together with plaster in contrast to the monumental ensembles in the north-east of the country from the period of the First Empire.[192] The gates and the more vulnerable sections were secured with pinnacled towers. The towers were usually rectangular in shape but there were also circular, oval, triangular, horseshoe-shaped or with irregular form.[192]

Religious architecture was very prestigious. The churches were among the most decorated and solid edifices in the country. Throughout the 13th and 14th centuries the basilicas were replaced with cruciform domed churches with one or three naves.[193] The exterior of the churches had rich decorative ornamentation in which belts of stone and brickwork alternated with each other. They further decorated with ceramic pieces in green, yellow and brown.[193] That feature is reflected in several churches in Messembria including the Church of St John Aliturgetos and the 14th century Church of Christ Pantocrator which had rows of blind arches, four-leaved floral motifs, triangular ornaments, circular turquoise ceramics and brick swastika friezes run along the external walls.[194] All of the over 20 churches in Tsarevets and many of the 17 churches in Trapezitsa were decorated with similar technique.[193] A typical characteristic of the Architecture of the Tarnovo Artistic School were the rectangular belfries above the narthex. Some churches such as Holy Mother of God in Asen's Fortress built during the Byzantine rule were reconstructed with belfry.[195]

The Church of the Holy Mother of God in Donja Kamenica in the western parts of the Bulgarian Empire (in modern Serbia) is notable for its unusual architectural style. Its twin towers are topped off by sharp-pointed pyramidal elements, with additional sharp-pointed details in each of the pyramids' four corners. The towers and their design were entirely unusual and unprecedented in medieval Bulgarian church architecture and were an influence from Hungary or Transylvania.[196]

Тhe Imperial Palace in Tarnovo was initially a bolyar castle and underwent two major reconstructions under Ivan Asen II (r. 1218–1241) and Ivan Alexander (r. 1331–1371). The palace had the shape of an irregular ellipse and built-up area of 5,000 sq.m.[195] The thickness of the walls reached two meters. The entrance gates were guarded by round and rectangular towers, the main entrance was located in the round tower of the northern façade. From the inside the edifices were built around an inner yard with the richly decorated royal church in the middle.[197] The Patriarch Palace was situated on the highest point of Tsarevets and dominated the city. Its plan resembled the one of the Imperial Palace and occupied 3,000 sq.m. A four-cornered bell-tower was adjoined to the Patriarchal Cathedral of the Holy Ascension of God. The residential and office sections were located in the southern part of the edifice.[198]

Few examples of nobility houses have survived. To the north of the Imperial Palace were excavated the foundations of a bolyar house from the beginning of the 13th century. It had a Г-shaped plan and consisted of residential area and a small one nave church.[199] There were two types of mass dwellings: semi-dug houses and overground houses. The latter were constructed in the cities and usually had two stories, the first one was built of crushed stones soldered with mud or plaster and the second one of timber.[199]

Art[edit]

The mainstream of Bulgaria's fine arts in the 13th and 14th centuries is referred to as the painting of the Tarnovo Artistic School and despite being influenced by some tendencies of the Palaeogan Renaissance in the Byzantine Empire, the Bulgarian painting had its own unique features and was first classified as a separate artistic school by the French art historian André Grabar.[200][201] The works of the school had some degree of realism, individualised portraits and psychological insight.[200][202]

Very little has remained of the secular art of the Second Empire. During excavations in the throne room of the Imperial palace in Tarnovo were uncovered fragments of murals depicting a richly decorated figure. The walls of the throne room were probably decorated with the images of Bulgarian emperors and empresses.[200]

An early example of the painting of the Tarnovo Artistic School are the frescoes in the Boyana Church near Sofia dated from 1259 which are among the most complete and well preserved monuments of east European medieval art.[203] Unlike contemporary Byzantine art and the church canon most of the 240 figures display individuality, psychological insight and vitality. Especially realistic are the portraits of the church's ktitors Kaloyan and Desislava, as well as the ruling monarch Constantine Tikh and his wife Irene, all dressed with ceremonial garments.[204] The Rock-hewn Churches of Ivanovo in the north-east of the country contain several churches and chapels with represent the evolution of the Bulgarian art in the 13th and 14th centuries. In the churches of the first period, painted during the reign of Ivan Asen II (r. 1218–1241), the human figures are depicted in realistic style, with oval faces and fleshy lips, and the colours of the clothing are bright, while the 14th-century frescoes are in the classical style of the Palaeogan period.[204][205] Both the Boyana Church and the Rock-Hewn Churches of Ivanovo are included in the UNESCO World Heritage List.[203][205]

In Tarnovo itself no complete painting ensemble has survived. The thirty-five scenes preserved in Holy Forty Martyrs Church feature the mild tones and sense of realism characteristic to the school.[200] In the ruined remains of the 17 churches in Tarnovo's second fortified hill, Trapezitsa, were unearthed fragments of frescoes, among them many depictions of military figures with richly decorated garments.[200] The palace chapel was decorated with mosaics.[206] In western Bulgaria there were some local characteristics which included archaism in the composition and unshaded tones. Examples of that art can be found in the Zemen Monastery, the Church of the Holy Mother of God in Donja Kamenica, the Church of St Peter in Berende, etc.[207]

Many books contained beautifully crafted miniatures, the most notable examples being the Bulgarian translation of the Manasses Chronicle, the Tetraevangelia of Ivan Alexander and the Tomić Psalter which combined have 554 miniatures.[208] The style of the miniatures was influenced by the contemporary Byzantine works. They cover a variety of theological and secular events and have significant aesthetic value.[209]

The Tarnovo school continued and enriched the traditions and icon design of the First Bulgarian Empire. Some notable icons include St Eleusa (1342) from Messembria which is currently kept in the Alexander Nevski Cathedral in Sofia and St John of Rila (14th century) kept in the Rila Monastery. Like the Boyana Church frescoes in the second one there is realism and non-canonical design.[210] Some of the preserved icons feature silver platings with enamel images of saints.[210]

Literature[edit]

The main centres of literary activity were the churches and monasteries which provided primary education throughout the country — writing and reading. Some monasteries rose to prominence providing what could be called secondary education which included advanced grammar, study of biblical, theological and ancient texts, as well as Greek language. Education was not restricted to the clergy and was available for laymen. Those who completed the advanced studies were called gramatik (граматик).[186] Initially books were written on parchment but the beginning of the 14th century saw the introduction of paper, imported via the port of Varna. At first paper was more expensive but by the end of the century the prices decreased which resulted in the production of larger quantities of books.[211]

Few texts dated from the 12–13th centuries have survived.[187] Notable examples from that period include the Book of Boril, an important source for the history of the Bulgarian Empire, and the Dragan Menaion which includes the earliest known Bulgarian hymnology and hymn tunes, as well as liturgies for Bulgarian saints — John of Rila, Cyril and Methodius and emperor Peter I.[212] Two poems of the period have survived, written by a Byzantine poet in the court in Tarnovo and dedicated to the wedding of emperor Ivan Asen II and Irene Komnene Doukaina. The emperor was compared to the sun and was described as "more lovely than the day, the most pleasant in appearance".[213]

During the 14th century literary activities were strongly supported by the court and in particular by emperor Ivan Alexander (r. 1331–1371), which combined with a number of prolific scholars and clergymen led to a remarkable literary revival,[186][187] known as the Tarnovo Literary School. Literature was also patronised by some nobles and rich citizens.[214] Literary work included translation of Greek texts and creating original compositions and was divided into religious and secular. The religious books included praising epistles, passionals, hagiographies, hymns and other. Secular literature included chronicles, poetry, novels, novelettes, apocryphical tales, popular tales, such as The Story of Troy and Alexandria, legal works, works on medicine and natural science, etc.[186]

The first notable scholar of that period was Theodosius of Tarnovo (d. 1363) who was influenced by Hesychasm and spread the hesyachastic ideas in Bulgaria.[176] His most prominent disciple was Euthymius of Tarnovo (c.1325–c.1403), Patriarch of Bulgaria (1375–1393) and founder of the Tarnovo Literary School.[208] A prolific writer, Euthymius oversaw a major linguistic reform creating a standardisation of the Bulgarian language both in term of spelling and grammar. Until the reform the texts often had variations on spelling and grammatical errors. The model of the reform was not the contemporary language but the language during the first golden age of Bulgarian culture in the late 9th and early 10th centuries during the First Bulgarian Empire.[215]

The Ottoman conquest of Bulgaria forced many scholars and disciples of Euthimius to emigrate bringing their texts, ideas and talent to the other Orthodox countries — Serbia, Wallachia, Moldavia and the Russian principalities. So many texts were brought to the Russian lands that scholar speak about a Second South Slavonic Influence on Russia.[216] The close friend and associate of Euthimius, Cyprian, became Metropolitan of Kiev and All Rus' and brought Bulgarian literary models and techniques.[187] Gregory Tsamblak worked in Serbia and Moldavia before assuming the position Metropolitan of Kiev. He wrote a number of sermons, liturgies and hagiographies, including Praising epistle for Euthymius.[187][217] Another important Bulgarian émigré was Constantine of Kostenets who worked in Serbia and whose biography of despot Stefan Lazarević is described by George Ostrogorsky as "the most important historical work of old Serbian literature".[218]

Apocryphal literature thrived in the 13th and 14th centuries. Apocryphal texts often concentrated on issues which were avoided in the official religious works. There were also many fortune-telling books which predicted events based on astrology and dreams.[219] Some of them included political elements such as a prophecy that if an earthquake would occur at night the people would get confused and would treat the emperor with disdain.[220] Apocryphal literature was condemned by the official authorities and was included in an index of banned books.[220] Nonetheless, it spread in Russia — the 16th century Russian noble Andrey Kurbsky called the apocryphs "Bulgarian fables".[220]

See also[edit]

Footnotes[edit]

Notes[edit]

^ a: Unlike the Byzantine Empire, the taxes in the First Bulgarian Empire were paid in kind.[13]

^ b: Peter I (r. 927–969) was the first Bulgarian ruler who received official recognition of his imperial title by the Byzantines and enjoyed great popularity during the Byzantine rule. Two other rebel leaders were proclaimed Emperor of Bulgaria under the name Peter before Theodore.[221]

^ c: The Roman and the Latin Empires were referred to by Western Europeans as "Romania".[222] The term "Franks" (in Bulgarian фръзи, in Greek frankoi) was used by the medieval Bulgarians and Byzantines to describe the whole Catholic population of Europe and the subjects of the Latin Empire.[223]

^ d: There is no information about territorial changes in the negotiations but many historians suggest that the Serbs occupied Niš at that time.[100]

^ e: When there was no legitimate heir of the deceased monarch it was customary that the nobility would elect an emperor among themselves. Constantine Tikh (r. 1257–1277), George I Terter (r. 1280–1292) and Michael Shishman (r. 1323–1330) were all elected emperors by the nobility.[124]

Citations[edit]

- ^ a b c Kamburova, Violeta (1992). Atlas "History of Bulgaria". Sofia: Bulgarian Academy of Sciences. pp. 18, 20, 23.

- ^ Тютюнджиев, Иван; Пламен Павлов (1992). Българската държава и османската експанзия 1369–1422 (in Bulgarian). Велико Търново.

- ^ Kǎnev, Petǎr (2002). "Religion in Bulgaria after 1989". South-East Europe Review (1): p. 81.

- ^ Obolensky, p. 246

- ^ Kazhdan 1991, pp. 334, 337

- ^ a b Fine 1987, p. 13

- ^ "Letters by the Latin Emperor Henry" in LIBI, vol. IV, Bulgarian Academy of Sciences, Sofia, p. 15

- ^ "Letters by the Latin Emperor Henry" in LIBI, vol. IV, Bulgarian Academy of Sciences, Sofia, p. 16

- ^ Kenrick, Donald (2004). Gypsies, from the Ganges to the Thames. University of Hertfodshire Press. p. 45. ISBN 1902806239.

- ^ "Encyclopædia Britannica: Vlach". Retrieved 20 September 2011.

- ^ Kolarz, Walter (1972). Myths and Realities in Eastern Europe. Kennikat Press. p. 217. ISBN 0804616000.

- ^ Boia, Lucian (1972). Romania: Borderland of Europe. p. 62.

- ^ a b Bozhilov & Gyuzelev 1999, pp. 342–343

- ^ Bozhilov & Gyuzelev 1999, p. 365

- ^ Bozhilov & Gyuzelev 1999, pp. 391–392

- ^ Andreev & Lalkov 1996, pp. 140, 143

- ^ Bozhilov & Gyuzelev 1999, p. 406

- ^ Fine 1987, p. 11

- ^ Fine 1987, p. 10

- ^ Andreev & Lalkov 1996, pp. 144, 149

- ^ Fine 1987, pp. 11–12

- ^ Vásáry 2005, p. 17

- ^ Andreev & Lalkov 1996, pp. 144–145

- ^ a b Andreev & Lalkov 1996, p. 150

- ^ Andreev & Lalkov 1996, pp. 150–151

- ^ Fine 1987, p. 14

- ^ Bozhilov & Gyuzelev 1999, p. 431

- ^ a b Andreev & Lalkov 1996, p. 151

- ^ Bozhilov & Gyuzelev 1999, pp. 431–432

- ^ Fine 1987, p. 15

- ^ Andreev & Lalkov 1996, pp. 153–155

- ^ Fine 1987, p. 16

- ^ a b Andreev & Lalkov 1996, p. 145

- ^ Bozhilov & Gyuzelev 1999, p. 434

- ^ Fine 1987, p. 27

- ^ Andreev & Lalkov 1996, pp. 156–157

- ^ Andreev & Lalkov 1996, pp. 146–147

- ^ Andreev & Lalkov 1996, p. 160

- ^ Fine 1987, p. 31

- ^ a b Andreev & Lalkov 1996, p. 162

- ^ Bozhilov & Gyuzelev 1999, p. 445

- ^ a b Andreev & Lalkov 1996, p. 165

- ^ Bozhilov & Gyuzelev 1999, pp. 445–446

- ^ a b c Fine 1987, p. 56

- ^ Andreev & Lalkov 1996, p. 167

- ^ Kazhdan 1991, p. 1095

- ^ Andreev & Lalkov 1996, pp. 168–171

- ^ Fine 1987, pp. 81–82

- ^ Andreev & Lalkov 1996, pp. 171–172

- ^ Bozhilov & Gyuzelev 1999, p. 457

- ^ Andreev & Lalkov 1996, pp. 180–183

- ^ Kazhdan 1991, p. 309

- ^ a b Andreev & Lalkov 1996, p. 185

- ^ Fine 1987, p. 120

- ^ Andreev & Lalkov 1996, pp. 188–189

- ^ Fine 1987, p. 124

- ^ Kazhdan 1991, p. 1134

- ^ Andreev & Lalkov 1996, p. 189

- ^ Fine 1987, p. 126

- ^ Fine 1987, p. 137

- ^ Fine 1987, p. 125

- ^ Andreev & Lalkov 1996, pp. 190–191

- ^ Fine 1987, p. 130

- ^ Andreev & Lalkov 1996, pp. 192–193

- ^ Vásáry 2005, p. 70

- ^ Fine 1987, p. 156

- ^ Andreev & Lalkov 1996, pp. 200–201

- ^ Fine 1987, pp. 156–157

- ^ a b Fine 1987, p. 159

- ^ Andreev & Lalkov 1996, pp. 204–205

- ^ Fine 1987, p. 172

- ^ Fine 1987, pp. 172, 174

- ^ Andreev & Lalkov 1996, p. 216

- ^ Fine 1987, pp. 176–177

- ^ Vásáry 2005, pp. 74–76

- ^ Andreev & Lalkov 1996, p. 218

- ^ Andreev & Lalkov 1996, pp. 222–223

- ^ Vásáry 2005, p. 80

- ^ Andreev & Lalkov 1996, pp. 224–226

- ^ Fine 1987, pp. 196–197

- ^ Vásáry 2005, p. 81

- ^ a b Andreev & Lalkov 1996, p. 227

- ^ Vásáry 2005, p. 83

- ^ Vásáry 2005, pp. 87–89

- ^ Fine 1987, p. 228

- ^ Andreev & Lalkov 1996, p. 247

- ^ Fine 1987, p. 229

- ^ Vásáry 2005, p. 110

- ^ Andreev & Lalkov 1996, pp. 248–250

- ^ Fine 1987, pp. 229–230

- ^ Andreev & Lalkov 1996, p. 250

- ^ Fine 1987, p. 230

- ^ Fine 1987, p. 269

- ^ Bozhilov & Gyuzelev 1999, p. 563

- ^ Bozhilov & Gyuzelev 1999, p. 566

- ^ Fine 1987, p. 270

- ^ Kazhdan 1991, p. 1365

- ^ Andreev & Lalkov 1996, p. 262

- ^ Andreev & Lalkov 1996, p. 266

- ^ a b c Fine 1987, p. 272

- ^ Andreev & Lalkov 1996, pp. 269–271

- ^ Andreev & Lalkov 1996, p. 272

- ^ Bozhilov 1994, pp. 194–195, 212

- ^ Andreev & Lalkov 1996, p. 273

- ^ Cox 1987, pp. 222–225

- ^ Andreev & Lalkov 1996, p. 275

- ^ Koledarov 1989, pp. 13–25, 102

- ^ Делев, Петър; Валери Кацунов; Пламен Митев; Евгения Калинова; Искра Баева; Боян Добрев (2006). "19. България при цар Иван Александър". История и цивилизация за 11-ти клас (in Bulgarian). Труд, Сирма.

- ^ a b Andreev & Lalkov 1996, p. 282

- ^ Bozhilov & Gyuzelev 1999, pp. 655–656

- ^ Fine 1987, p. 407

- ^ Fine 1987, p. 266

- ^ Fine 1987, p. 367

- ^ Jireček 1978, p. 387

- ^ Andreev & Lalkov 1996, pp. 283–284, 286

- ^ Bozhilov & Gyuzelev 1999, pp. 662–663

- ^ Bozhilov & Gyuzelev 1999, p. 666

- ^ Andreev & Lalkov 1996, p. 297

- ^ Fine 1987, pp. 424–425

- ^ Bozhilov 1994, p. 237

- ^ Pavlov 2008, p. 218

- ^ a b Petrov & Gyuzelev 1978, p. 608

- ^ Bakalov & co 2003, p. 402

- ^ a b Bakalov & co 2003, p. 403

- ^ Petrov & Gyuzelev 1978, pp. 611–612

- ^ Petrov & Gyuzelev 1978, p. 618

- ^ a b Bakalov & co 2003, p. 404

- ^ Bakalov & co 2003, pp. 404–405

- ^ Koledarov 1989, p. 12

- ^ Petrov & Gyuzelev 1978, p. 615

- ^ Koledarov 1989, pp. 9–10

- ^ a b Koledarov 1989, p. 10

- ^ Petrov & Gyuzelev 1978, pp. 615–616

- ^ Angelov & co 1982, p. 193

- ^ Angelov & co 1982, p. 203

- ^ Angelov & co 1982, pp. 203–205

- ^ a b Andreev & Lalkov 1996, p. 166

- ^ a b c Andreev & Lalkov 1996, p. 269

- ^ Cited in Халенбаков, О. Детска енциклопедия България: Залезът на царете, с. 18

- ^ Koledarov 1989, pp. 13, 26–27

- ^ Andreev & Lalkov 1996, pp. 167–169

- ^ Nicolle, David; Angus McBride (1988). Hungary and the Fall of Eastern Europe 1000-1568. Osprey Publishing. p. 24.

- ^ "Imago Mundi by Honorius Augustodunensis" in LIBI, vol. III, Bulgarian Academy of Sciences, Sofia, p. 66

- ^ "History of the Crusade of Emperor Frederick I by Ansbert" in LIBI, vol. III, Bulgarian Academy of Sciences, Sofia, p. 267

- ^ Angelov 1950, p. 428

- ^ Angelov 1950, p. 429

- ^ "History of the Crusade of Emperor Frederick I by Ansbert" in LIBI, vol. III, Bulgarian Academy of Sciences, Sofia, p. 283

- ^ Petrov & Gyuzelev 1978, p. 238

- ^ Angelov 1950, p. 431

- ^ Petrov & Gyuzelev 1978, pp. 266, 293–294

- ^ Lishev 1970, p. 84

- ^ Petrov & Gyuzelev 1978, p. 293

- ^ "Historia by Nicetas Choniates" in GIBI, vol. XI, Bulgarian Academy of Sciences, Sofia, p. 88

- ^ Lishev 1970, p. 91

- ^ Dochev 1992, p. 312

- ^ Radushev 1990, pp. 10, 13

- ^ Dochev 1992, pp. 181–183

- ^ Dochev 1992, pp. 183–184

- ^ Radushev 1990, p. 21

- ^ Dochev 1992, p. 313

- ^ Radushev 1990, pp. 15, 21

- ^ Bozhilov & Gyuzelev 1999, pp. 444–445

- ^ Fine 1987, p. 55

- ^ Bozhilov & Gyuzelev 1999, p. 446

- ^ Duychev 1972, p. 426

- ^ Duychev 1972, pp. 426–427

- ^ a b Duychev 1972, p. 430

- ^ Zlatarski 1972, p. 535

- ^ Bozhilov & Gyuzelev 1999, p. 514

- ^ Zlatarski 1972, pp. 536–537

- ^ Zlatarski 1972, pp. 596–602

- ^ a b c "History of the Bulgarian Orthodox Church". Official Site of the Bulgarian Patriarchate (in Bulgarian). Retrieved 2 February 2014.

- ^ Bakalov & co 2003, p. 445

- ^ Fine 1987, p. 437

- ^ a b Bozhilov & Gyuzelev 1999, p. 619

- ^ a b Fine 1987, pp. 439–440

- ^ a b Kazhdan 1991, p. 301

- ^ Bozhilov 1994, p. 71

- ^ Bozhilov & Gyuzelev 1999, pp. 470–471

- ^ Fine 1987, p. 100

- ^ Bozhilov & Gyuzelev 1999, p. 471

- ^ Fine 1987, p. 441

- ^ Fine 1987, p. 442

- ^ a b Bozhilov & Gyuzelev 1999, p. 620

- ^ Fine 1987, p. 435

- ^ a b c d Fine 1987, p. 436

- ^ a b c d e f Kazhdan 1991, p. 337

- ^ Bozhilov & Gyuzelev 1999, pp. 620–621

- ^ Angelov & co 1982, p. 379

- ^ Bakalov & co 2003, pp. 426–427

- ^ Bakalov & co 2003, pp. 427–428

- ^ a b c Angelov & co 1982, p. 381

- ^ a b c Angelov & co 1982, p. 382

- ^ Nikolova 2002, pp. 147–148

- ^ a b Angelov & co 1982, p. 384

- ^ Nikolova 2002, p. 116

- ^ Angelov & co 1982, pp. 384–385

- ^ "Патриаршеската катедрала "Свето Възнесение Господне"" [The Patriarchal Cathedral of the Holy Ascension of God] (in Bulgarian). Православие. Archived from the original on 8 November 2014. Retrieved 8 November 2014.

- ^ a b Angelov & co 1982, p. 385

- ^ a b c d e Angelov & co 1982, p. 389

- ^ Grabar, André (1928). La peinture religiouse en Bulgarie (in French). Paris. p. 95.

- ^ Tsoncheva 1974, p. 343

- ^ a b "Boyana Church". Official Site of UNESCO. Retrieved 4 November 2014.

- ^ a b Angelov & co 1982, p. 390

- ^ a b "Rock-Hewn Churches of Ivanovo". Official Site of UNESCO. Retrieved 4 November 2014.

- ^ Angelov & co 1982, pp. 389–390

- ^ Angelov & co 1982, p. 391

- ^ a b Bozhilov & Gyuzelev 1999, p. 622

- ^ Bozhilov & Gyuzelev 1999, pp. 622–624

- ^ a b Angelov & co 1982, p. 392

- ^ Fine 1987, pp. 436–437

- ^ Иванов, Йордан (1970). Български старини из Македония (in Bulgarian). Sofia: Българска академия на науките. pp. 296–305, 359–367, 387–390.

- ^ Angelov & co 1982, p. 429

- ^ Angelov & co 1982, p. 431

- ^ Fine 1987, pp. 442–443

- ^ Fine 1987, p. 444

- ^ Fine 1987, pp. 444–445

- ^ Ostrogorsky, George (1969). History of the Byzantine State. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press. p. 476.

- ^ Angelov & co 1982, pp. 448–449

- ^ a b c Angelov & co 1982, p. 449

- ^ Andreev & Lalkov 1996, p. 144

- ^ Kazhdan 1991, p. 1805

- ^ Kazhdan 1991, p. 803

Sources[edit]

References[edit]

- Андреев (Andreev), Йордан (Jordan); Милчо Лалков (Milcho Lalkov) (1996). Българските ханове и царе (The Bulgarian Khans and Tsars) (in Bulgarian). Велико Търново (Veliko Tarnovo): Абагар (Abagar). ISBN 954-427-216-X.

- Ангелов (Angelov), Димитър (Dimitar); Соня Георгиева (Sonya Georgieva), Васил Гюзелев (Vasil Gyuzelev), Любомир Йончев (Lyubomir Yonchev), Страшимир Лишев (Strashimir Lishev) и колектив (1982). История на България. Том III. Втора българска държава (History of Bulgaria. Volume III. Second Bulgarian State) (in Bulgarian). Sofia: Издателство на БАН (Bulgarian Academy of Sciences Press).

- Ангелов (Angelov), Димитър (Dimitar) (1950). По въпроса за стопанския облик на българските земи през XI–XII век (On the Issue about the Economic Outlook of the Bulgarian Lands during the XI–XII centuries) (in Bulgarian). ИП (IP).

- Бакалов (Bakalov), Георги (Georgi); Петър Ангелов (Petar Angelov), Пламен Павлов (Plamen Pavlov), Тотю Коев (Totyu Koev), Емил Александров (Emil Aleksandrov) и колектив (2003). История на българите от древността до края на XVI век (History of the Bulgarians from Antiquity to the end of the XVI century) (in Bulgarian). София (Sofia): Знание (Znanie). ISBN 954-621-186-9.

- Bogdan, Ioan (1966). Contribuţii la istoriografia bulgară şi sârbă în Scrieri alese (Contributions from the Bulgarian and Serbian Historiography in Selected Writings) (in Romanian). Bucharest: Anubis.

- Божилов (Bozhilov), Иван (Ivan) (1994). Фамилията на Асеневци (1186–1460). Генеалогия и просопография (The Family of the Asens (1186–1460). Geneaology and Prosopography) (in Bulgarian). София (Sofia): Издателство на БАН (Bulgarian Academy of Sciences Press). ISBN 954-430-264-6.

- Божилов (Bozhilov), Иван (Ivan); Васил Гюзелев (Vasil Gyuzelev) (1999). История на средновековна България VII–XIV век (History of Medieval Bulgaria VII–XIV centuries) (in Bulgarian). София (Sofia): Анубис (Anubis). ISBN 954-426-204-0.

- Cox, Eugene L. (1987). The Green Count of Savoy: Amadeus VI and Transalpine Savoy in the Fourteenth Century. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press.

- Дочев (Dochev), Константин (Konstantin) (1992). Монети и парично обръщение в Търново (XII–XIV век) (Coins and Monetary Circulation in Tarnovo (XII–XIV centuries)) (in Bulgarian). Велико Търново (Veliko Tarnovo).

- Дуйчев (Duychev), Иван (Ivan) (1972). Българско средновековие (Bulgarian Middle Ages) (in Bulgarian). София (Sofia): Наука и Изкуство (Nauka i Izkustvo).

- Fine, J. (1987). The Late Medieval Balkans, A Critical Survey from the Late Twelfth Century to the Ottoman Conquest. University of Michigan Press. ISBN 0-472-10079-3.

- Георгиева (Georgieva), Цветана (Tsvetana); Николай Генчев (Nikolay Genchev) (1999). История на България XV–XIX век (History of Bulgaria XV–XIX centuries) (in Bulgarian). София (Sofia): Анубис (Anubis). ISBN 954-426-205-9.